John Speed is almost certainly the most famous of all English map-makers. He was the author of the most important, and prestigious atlas of his day, and his maps still find favour today, with collectors from all over the world. Speed is best known today for two atlases, the Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, published in 1612, and the Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World, published in 1627. The latter is attributed to Speed in the title, although it is not certain how large a contribution he actually made.. Thus, it is really on the Theatre that his contribution to English cartography must be judged.

John Speed – The Man

“John Speed, who was bred a Tailor, was by the generosity of Sir Fulk Grevil, his patron, set free from a manual employment and enabled to pursue his studies, to which he was strongly inclined by the bent of his genius. The fruits of them were his Theatre of Great Britain, containing an entire set of maps of the counties drawn by himself, his History of Great Britain, richly adorned with seals, coins & medals, from the Cotton collection; and his Genealogies of Scripture, first bound up with the Bible, in 1611 which was the first edition of the present English translation. His maps were very justly esteemed & his History of Great Britain, was, in its kind incomparably more complete, than all the histories of his predecessors put together …”

This brief note, from Granger’s Bibliographical History of England (1779) includes most of what little information we know of Speed. Unfortunately, an earlier note, in Thomas Fuller’s The History of the Worthies of England (1662) records even less detail, despite the author having talked to one of Speed’s daughters.

Speed was born at Farndon, Cheshire, in 1552, and settled in London, in about 1582. He died on July 28th, 1629, and was buried in the Church of St. Giles, in Cripplegate.

A monument was erected to him in the church, comprising a bust, flanked by two stone doors, with inscriptions. The doors were destroyed by bombing in the Second World War, but the bust, although damaged, survived. Fortunately, an engraving, from John Thomas Smith’s Antiquities of London (London, 1791), depicts the monument and inscriptions.

While earning a living as a tailor, Speed developed a strong interest in history, particularly antiquities and genealogies. His first cartographical work, a four sheet wall map of Canaan in Biblical Times, was published in 1595. Shortly after, in 1598, Speed came to the attention of Sir Fulke Greville. Through Greville’s patronage, Speed received a sinecure appointment with the Customs Service, which guaranteed him a living, while giving him the freedom to pursue his interests. In the text accompanying his map of Warwickshire, Speed acknowledged this debt:

Whose merits to me-ward I do acknowledge in setting this hand free from the daily imployments of a manuall Trade, and giving it his liberty thus to express the inclination of my mind, himself being the procurer of my present Estate

Speed was also introduced into Greville’s circle of friends, and sponsored for membership of the Society of Antiquaries. There he met many of the greatest scholars of the day, including William Camden, Robert Cotton and William Smith, all of whom later contributed to Speed’s work. One can only guess that it was at this time that Speed received the encouragement to undertake his great project – the History of Great Britain, with an accompanying atlas volume, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine. In 1600, Speed donated a number of maps to the Merchant Taylors Company, who noted his “very rare and ingenious capacitie in drawing and setting forth of mappes and genealogies and other very excellent inventions” (1).

In the Proeme to the History (1611), Speed implied that he had spent a large number of years in compiling the History and the Theatre, and in the introduction to the Theatre, he wrote:

“So great was the attempt to assay the erection of this large and laborious Theatre, . . . that even in the entrance of the first draught as one altogether discouraged, I found my selfe farre unfit and unfurnished both of matter and meanes, either to build or beautifie so stately a project.”

The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine

While Speed was involved in assembling the materials for his books, he needed a commercial partner to supervise publication, and for this he turned to John Sudbury and George Humble. As the largest and most successful publishers and print-sellers in London, Sudbury and Humble were perhaps the only publishers of the day able to undertake such a grand project. The partnership was established in 1599, when George Humble joined his uncle John Sudbury in business, in the latter’s premises in Popes Head Alley near the Royal Exchange. Thus came into being the “first English firm to specialize in the sale of engravings, maps and copy-books”. (2) The main foundation of their business was the publication of separate prints, primarily portraits, but they also had experience of book-publishing having, for example, re-issued Stephen Harrison’s The Arches of Triumph, in 1604, with seven plates depicting the triumphal arches erected to welcome the new King, James I, to London in 1603.

In about 1604, the first manuscript map was ready, and given to William Rogers, the most talented English engraver of the period, to engrave. The county chosen was Cheshire, no doubt because Speed, being a native of the county (as was Rogers), felt most confident in the completed delineation. Rogers was presumably to engrave the whole series, but his death, in 1604, ended early attempts to complete the atlas. Today, only two copies of this map are known, in proof collections of the Theatre. In formal editions, a newly engraved map of Cheshire was used, apparently to ensure uniformity throughout the series.

Following the death of Rogers, Sudbury and Humble were compelled to look abroad -to the gifted Flemish engraver Jodocus Hondius Sr. (1563-1612), who was establishing himself as the leading engraver and mapmaker in Amsterdam. Hondius was in many ways also an obvious choice, having lived in England from 1583 to 1593. In that period, he engraved a number of maps and prints, including three of the charts in The Marriners’ Mirrour, (1588), a World map depicting Drake’s circumnavigation, and a portrait of that English hero. He also made the acquaintance of a number of figures involved in Speed’s project. Thus it was that on April 27th 1607, William Camden wrote a letter of introduction for Speed to Hondius, urging Hondius to assist in preparing the maps.

Between 1607 and 1611 (the date on the plate of the Royal Arms), Hondius worked on the many map-plates, title plates and so on, for the Theatre and History. While the actual terms of the contract are not known, one can assume that he was employed, by Sudbury and Humble, to engrave the title, Royal Arms and sixty-seven maps for the Theatre, and that on completion, the plates would be sent to London, to be printed. Speed’s note in the introduction to the Theatre that he “knew not what I undertooke, untill I saw the charges thereof (by others bestowed) to amount so high” may well refer to this contract.

On April 7th 1608, George Humble registered for a Royal License, or privilege “for twenty-one years to print a book compiled by John Speed called ‘The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britayne” with cartes and maps ..”. Unfortunately, while both Sudbury and Humble had backgrounds in the book, neither was a member of the Stationers’ Company, so their names and activities do not figure in the various volumes of records kept by the Company in that period.

Many of the early proof sheets are dated 1608 (for example Essex, Dorset and Lancashire) so it would seem that the publishers had hoped to issue the Theatre that year. Presumably, difficulties caused by the geographical separation of Hondius from his principals slowed the process down, and this may explain the large number of sets of proofs that survive, as the manuscripts were sent to Amsterdam, and then printed proofs were sent backwards and forwards between London and Amsterdam for correction.

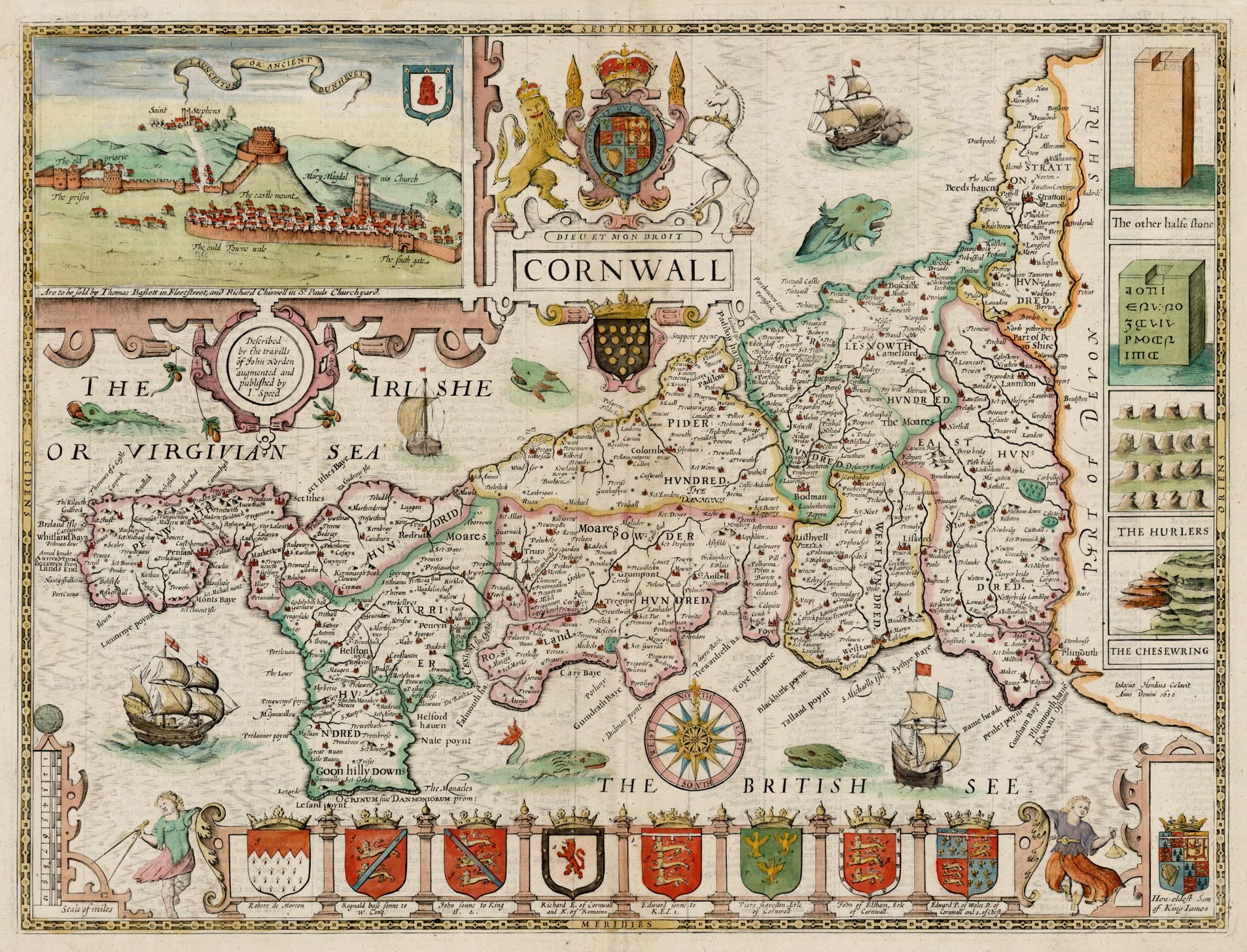

and Speed’s text passed to William Hall and John Beale for type-setting. Although the engraved title-page for the Theatre was dated 1611, the subsidiary titles for the third and fourth books, respectively Scotland and Ireland, were dated 1612. In the meantime, it is probable that the maps were available for sale individually, as is implied by the lengthy address found on some maps, such as the Cornwall: “Theise Mappes are to be solde in Popes-heade alley against ye Exchange by John Sudbury and G. Humble. Cum Privilegio”. Normally, atlas maps would carry only a very abbreviated publisher’s imprint, with the full address found on the title-page. Evidently, Sudbury and Humble’s background as print-sellers encouraged the separate sale of maps as a way of recouping some of their initial investment.

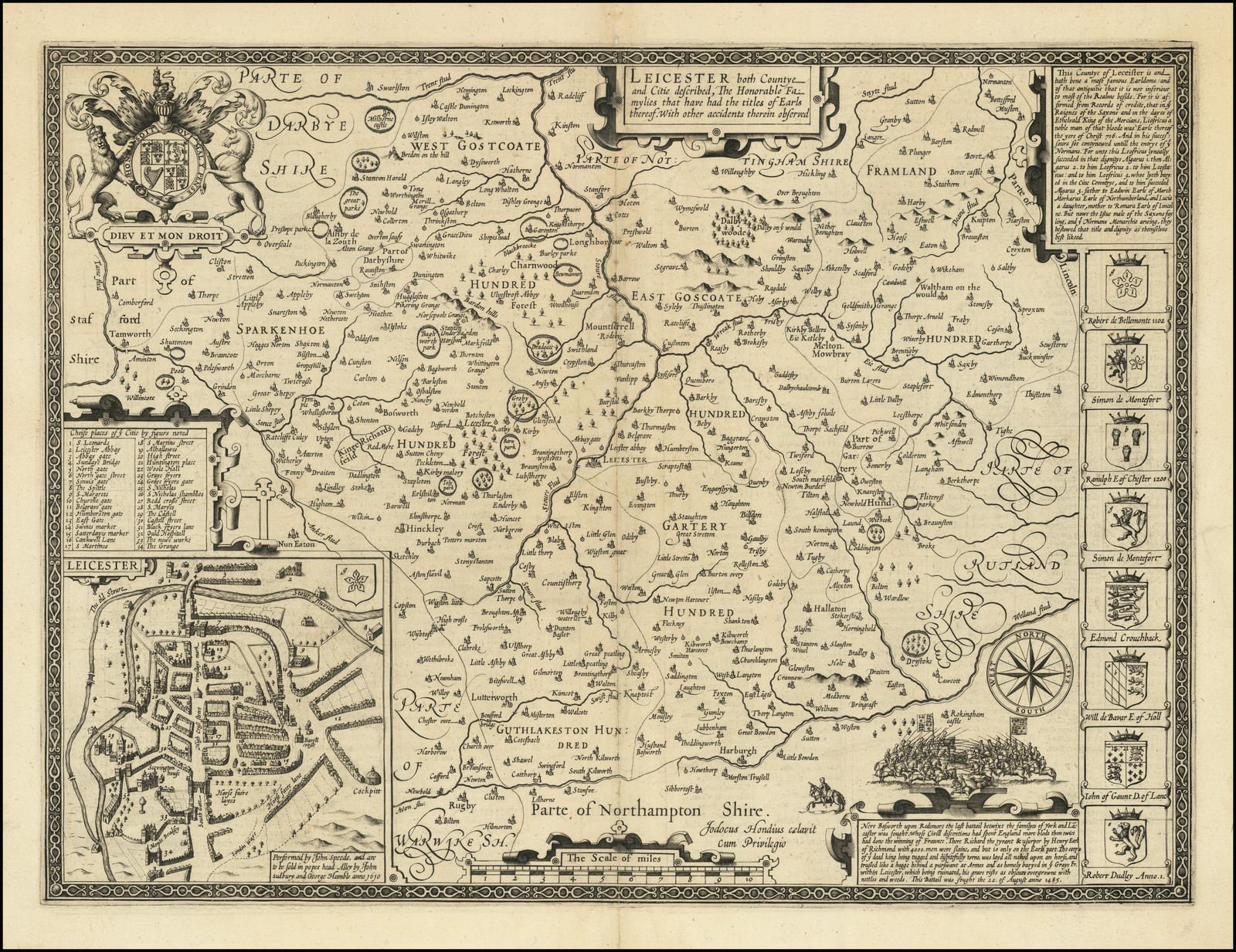

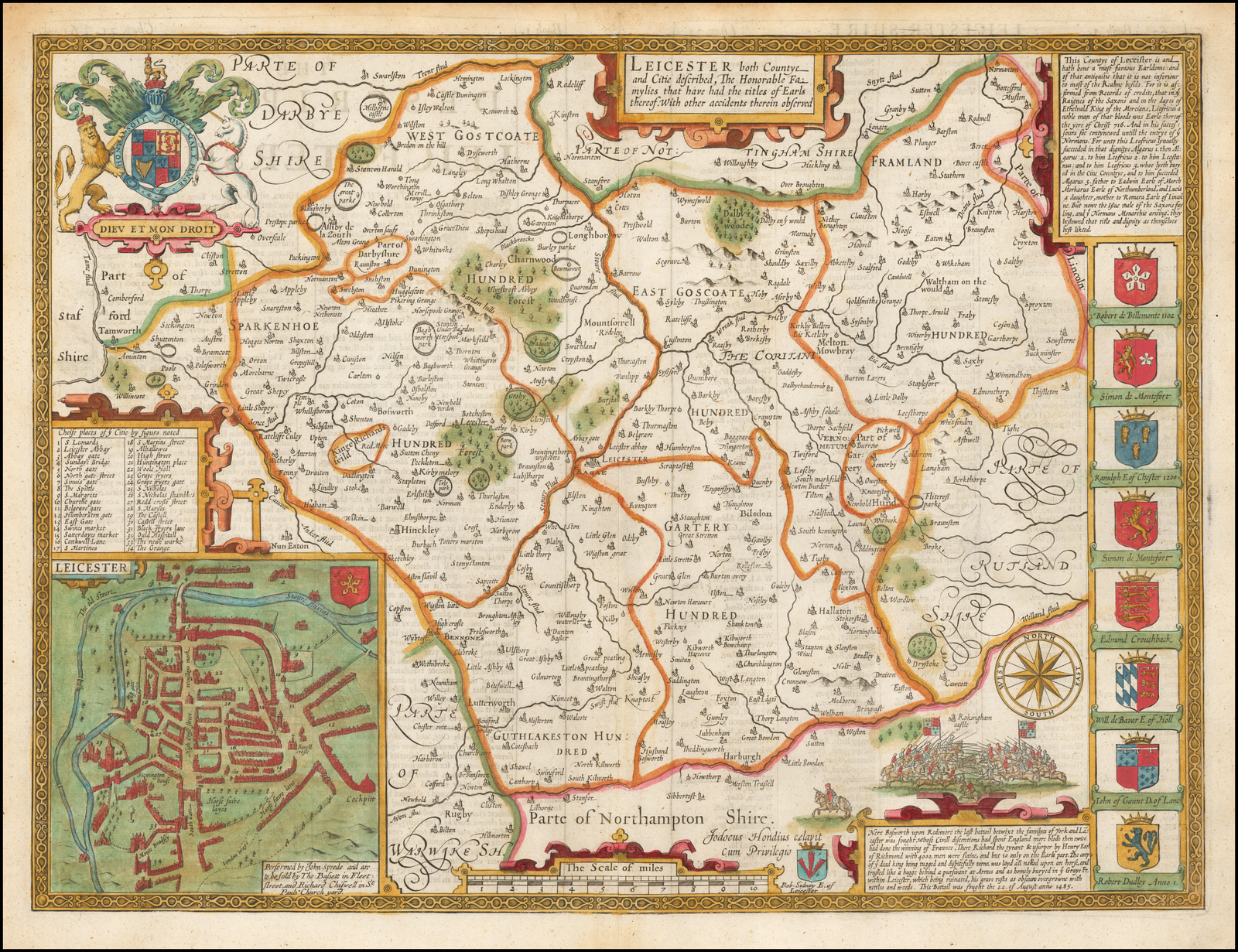

We do not know the price for which the First Edition sold, but the 1627 edition of the Theatre was offered at 40 shillings bound, 30 shillings unbound, and the History for 30 shillings bound, 20 shillings unbound. In much the same way, the atlas could be purchased with the maps either in black and white or coloured. Colouring could take two forms. The simpler would involve the application of outline colour to the body of the map, and full colour to the decorative elements.

The more expensive option was to have the map and the decorative elements in full colour. While many examples were sold black and white, the publishers clearly made preparations to enable the maps to be coloured quickly and accurately. Hondius was supplied with detailed illustrations of the armorials to be added to the maps. Using standard conventions, an engraver could designate colours for each part of a shield by nuances of hatchuring, stippling and so on, which the colourist would interpret to ensure accuracy.

Certainly, the application of colour enhances the visual appeal of the maps, highlighting borders, boundaries, the coats of arms and so on. However, the expense of the colouring was to be borne by the purchaser also. Although most of the evidence for the costs involved comes from the latter part of the seventeenth century, it would seem that a folio map in colour cost about half as much again as a black and white example. If this ratio is broadly correct, as a proportion, for the 1610’s as it is for the 1670’s, then colouring might well have added about ten or fifteen shillings to the purchase price, and would explain why so few copies were coloured at the time.

Unfortunately, there are no surviving records of how many examples of the First Edition (or indeed of any edition) were printed. One might speculate that the First Edition could have numbered between about five hundred and one thousand examples. It should be remembered that market for maps was not well developed in England in 1612. This, together with the cost of the atlas, the need for a second edition soon afterwards, and the high quality of impressions from the third, Latin text, edition of 1616, suggests that the first print-run may have been closer to five hundred copies or so. Unfortunately, until an attempt is made at a census of surviving examples, these figures can be regarded as only the roughest of estimates. Nevertheless, with the exception of the Basset and Chiswell edition of 1676, the First Edition was the largest printing of the Theatre.

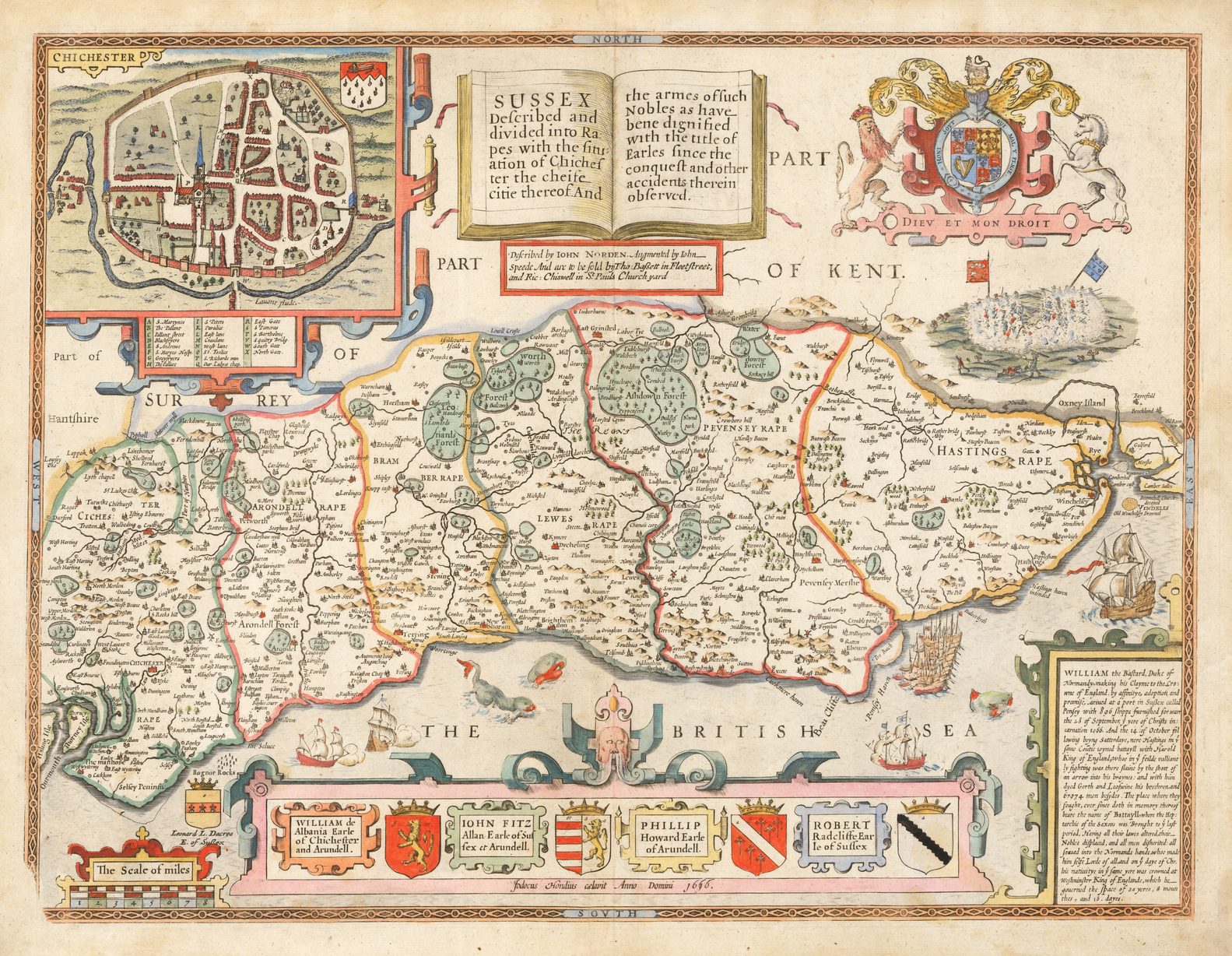

The Theatre was a great success. It was the first atlas of the British Isles, and it was the first attempt by an Englishman at atlas production on a scale comparable with the great continental publishing houses. The individual maps are a tribute to Speed’s skills and interests, successfully balancing the desire to produce modern maps of the counties, with his personal interest in the antiquities of the British countryside. Within the blank areas outside the maps, Speed managed to insert a great deal of information on antiquarian remains, and thus created arguably the most decorative sets of maps of the English counties to appear. The antiquarian material relates primarily from the Roman period, whether the section of Watling Street in Huntingdonshire, or the course of Hadrian’s Wall in the maps of Cumberland and Northumberland, but does include pre-historic remains, such as Stonehenge, and the sites of famous battles, such as Tewkesbury, St. Albans, Evesham, and the Norman landing at Pevensey.

Also reflecting his interests, Speed included “The armes of such Princes and Nobles as have had the dignities, and borne the titles either of Dukes, Marquesses, or Earles, in the same Province, City or Place.” Much of this information was supplied by William Smith, the College of Arms’ RougeDragon, and an important contributor to the Theatre, a debt acknowledged in the Conc1usion to the History.

The high cost of the Theatre would have restricted not only the circulation of the atlas, but also its use. The Theatre was essentially a library volume, to be examined in a study, not a traveller’s aid. In particular, with the exception of the Roman Watling Street, no roads are marked on the map. This rather leads to the question, what exactly was the atlas for, and how did the principal participants view it. Speed himself saw it as an adjunct of his History, and the two volumes together as a means of communicating his deep interest in the antiquities and history of England to a larger audience. In the History, he wrote;

“But by what fate I am forced still to goe on, I know not unlesse it be the ardent affection and love to my native country; … That this our Country and subject of History deserveth the love of her inhabitants, is witnessed even by forraine writers themselves, who have termed it the Court of Queen Ceres, the Granary of the Westerne World, the fortunate Island, the Paradise of pleasure and Garden of God …“

Sudbury and Humble would have realised the commercial potential, particularly in light of the patronage enjoyed by Speed, with the added advantage of broadening their stock to encompass the full range of graphic arts, and this mix of maps and prints can be seen in the stock-in-trade of the majority of subsequent seventeenth century print-sellers in London.

Speed’s backers also had their own perspective, which was essentially political in tone, and Speed conveyed this sentiment n the introduction to the Theatre, where he extolled the present, peaceful, condition of England, compared to the more turbulent past:

“Where we from under oure owne vines without feare may behold the prints or indured miseries, sealed with the blood of those times, to the losse of their lives, and liberties; our selves heare not the sound of the Alaru[m] in our Gates, nor the clattering of armor in our campes, whose swords are now turned into mattockes and speares into sithes…“

Speed’s patrons, loyal supporters of the Crown, wished to contrast the relative stability achieved by the Houses of Tudor and Stuart, with the many civil wars, which had culminated in the Wars of the Roses, between the Houses of York and Lancaster. In the most elaborate of the county maps, that of Lancashire, Speed inserted portraits of the Yorkist and Lancastrian protagonists, ending with Henry Tudor, and his bride, Elizabeth, a marital alliance that reconciled the two factions under Henry, as Henry VII.

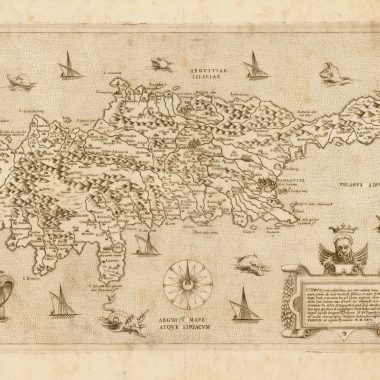

Within both books, a sense of natural historical progression is encouraged, and this is best exemplified by the juxtaposition of the map of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, with the contemporary map of the British Isles. The former depicts the division of England and Wales between the seven rival Anglo-Saxon dynasties. Along the left hand border are vignette scenes illustrating the founders of each of the kingdoms. Along the right hand border are seven vignettes, showing the conversion of each kingdom to Christianity, again imbuing a sense of progression or development. The modern map, ‘The Kingdome Of Great Britain And Ireland’ represents symbolically the unification of the British Isles under one crown, with the accession of James VI of Scotland to the English throne as James I, in lawful succession to Elizabeth. This map also served to portray the English counties as parts of an integral whole.

Just as Lord Burghley viewed Christopher Saxton’s county maps as a “tool of administrative control”, so too Speed’s maps would have served the same purpose for the administrators of Stuart government, with the considerable amount of information on the administrative divisions of the counties, inserted by Speed from the Parliamentary Rolls, and the Nomina Villarum kept by local sheriffs. Where possible, for each county, Speed showed “The Shire divisions into Lathes, Hundreds, Wapentakes and Cantreds, according to their ratable and accustomed manner.”

One problem with assessing Speed’s personal achievement is gauging the extent of his contribution to the Theatre. Skelton summarised thus: “Little of his cartographic work on the county maps seems to have been original; the phrase ‘Performed by John Speed’, which occurs on most of the maps not explicitly ascribed to any cartographer, may be taken to mean that he copied, adapted or compiled from the work of others”. (3) Speed himself admitted, in the introductory text to the Theatre, that “it may be obiected that I have put my sickle into other mens corne, and have laid my building upon other mens foundations.”

However, Speed did introduce notable improvements to his source maps, as he noted in the introduction:

“The Shires divisions into Lathes, Hundreds, Wapentakes and Cantreds according to their ratable, and accustomed manner I have separated, and under the same Title that the record beareth, in their due places distinguished; wherein by the helpe of the Tables annexed, any Citie, Towne, Burrough, Hamlet, or place of note may readily be found, and whereby safely may be affirmed that there is not any one kingdome in the world so exactly described …“

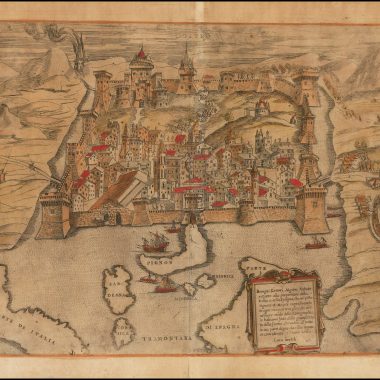

An even more notable improvement was the introduction of town plans:

“The true plot of the whole land, & that again into parts in several Cards are described, as likewise the cities and shire townes are inserted, whereof some have bene performed by others, without Scale annexed, the rest by mine owne travels, and unto them for distinctions sake, the Scale of Pases, accounted according to the Geometrical measure, five foote to a pace I have set …”

While he may have taken the idea from the inset plan of Chichester on Norden’s map of Sussex, Speed went far further, assembling the first printed collection of town plans of the British Isles, of which perhaps as many as fifty, of the seventy-three, had not previously been mapped. Speed only claimed to have personally mapped two towns. In the title of the map of Pembroke, the insets of Pembroke and St. Davids are described as “shewed in due form as they were taken by John Speed”, but the appearance of the “Scale of Pases”, on fifty-one of the plans, implies a much greater contribution on his part.

While it would be easy to characterize Speed as a plagiarist, it should be noted that many of the authorities, from whom Speed borrowed, actively assisted him in this great project. They obviously felt no wrong done to them, and nor did near-contemporary commentators, such as Thomas Fuller, judge him harshly on this account. Fuller wrote:

“This is he [ie Speed] who afterwards designed the Maps and composed the History of England, though much help’d in both (no shame to crave aid in a work too weighty for any ones back to bear) by Sir Robert Cotton, Master Camden, Master Barkham, and others.”

Indeed, Speed was fulsome in his giving credit to his sources, writing:

“The further descriptions of sundry provinces I have gleaned from the most famous workes of the most worthy and learned Cambden, whose often sowed seedes in that soile hath lastly brought forth a most plenteous harvest. For the body of the Historie, many were the manuscripts, notes and Records wherewith my honoured and learned friends supplied me; but none more (and so many) as did the worthy repairer of eating times ruines, the learned Sir Robert Cotton Knight Baronet, . . . whose Cabinets were unlocked, and Library continually put open to my free accesse: & from where the cheifest garnishments of this work have been enlarged and brought. …”

Rather, Speed’s achievement was to bring together so much material – historical texts, illustrations of coins, antiquities and remains, armorial designs, genealogical and cartographical information – and blending it all together into two such outstanding volumes, which earned the immediate respect of his contemporaries, and that have given such pleasure, both textually and visually, to successive generations ever since.

Although Speed, personally, viewed the History as the more important work, it was the Theatre that captured the attention of his contemporaries and successors. Despite the fact that Speed’s maps were derivative of other series, particularly Saxton, it was his maps that served as the basis for subsequent folio county atlases, up until Bowen and Kitchin’s series of maps for the Large English Atlas, engraved between 1749 and 1760.

The printing plates were frequently re-printed, as they passed between successive publishers, with the last printing from them being between about 1756 and about 1770, nearly one hundred and fifty years after they first appeared. By this time, their primary interest was antiquarian, rather than geographical, but one can imagine Speed approving of this.

NOTES

1. Hind, Arthur Engraving in England in the Sixteenth & Seventeenth Centuries, vol. II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1955) II, p.68.

2. Rostenberg, Leona English Publishers in the Graphic Arts 1599-1700 (New York, 1963), p.1.

3. Skelton, R.A. County Atlases of the British Isles 1579-1703 (London, 1970), p.31-2.

1 comment