While engraving became the predominant technique for the production of printing maps in the period 1472 to 1830, in the early period, from 1472 to about 1570, woodcut was also a very popular medium for as a printing platform for maps and prints.

While there are obvious exceptions, early publishers north of the Alps frequently used woodcuts for their books and atlases, while their Italian counterparts preferred engraving. For the fifteenth century, Tony Campbell noted: “The copy of Breydenbach’s map of Palestine in the 1488 edition of Le Huen was…the only engraved incunable map prepared north of the Alps. If the simple diagrams are ignored, fifteenth-century printed maps neatly divide into Italian engraving and German woodcut” (1).

A Very Brief Summary Of The History Of Woodcut Maps 1472-1590

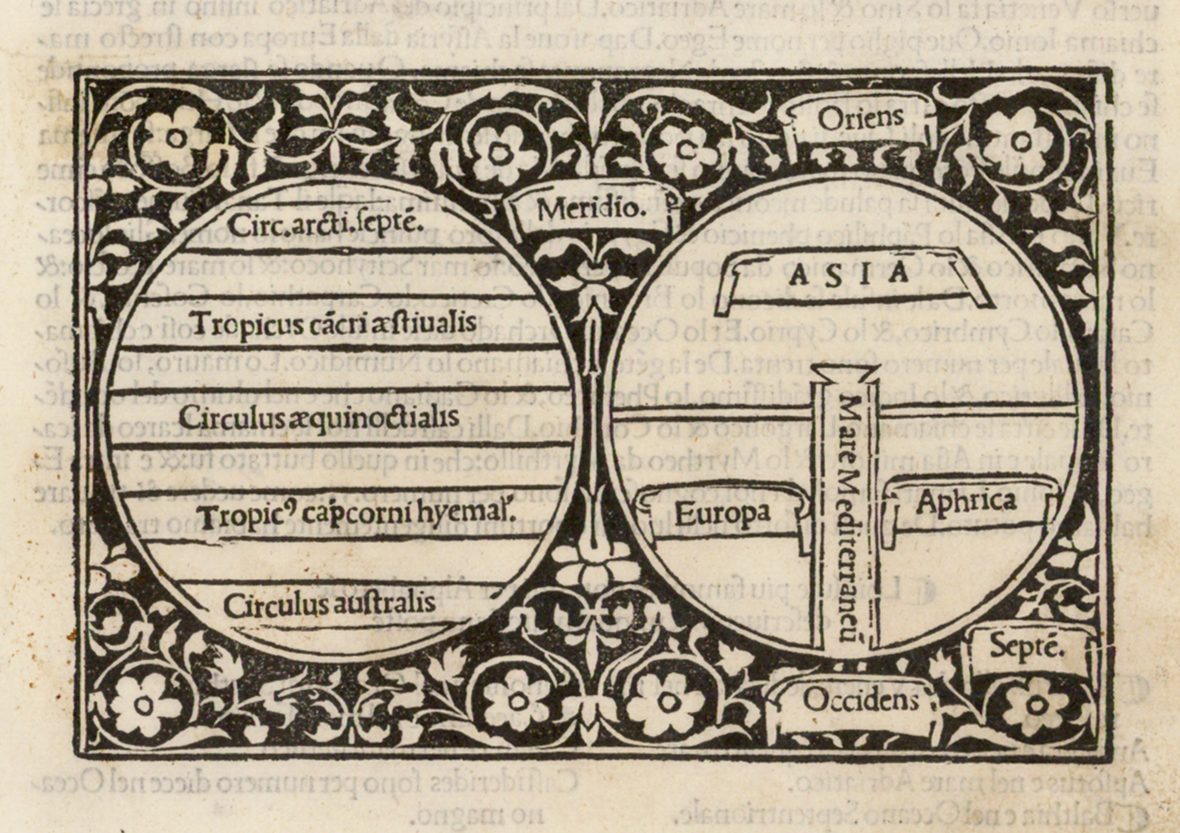

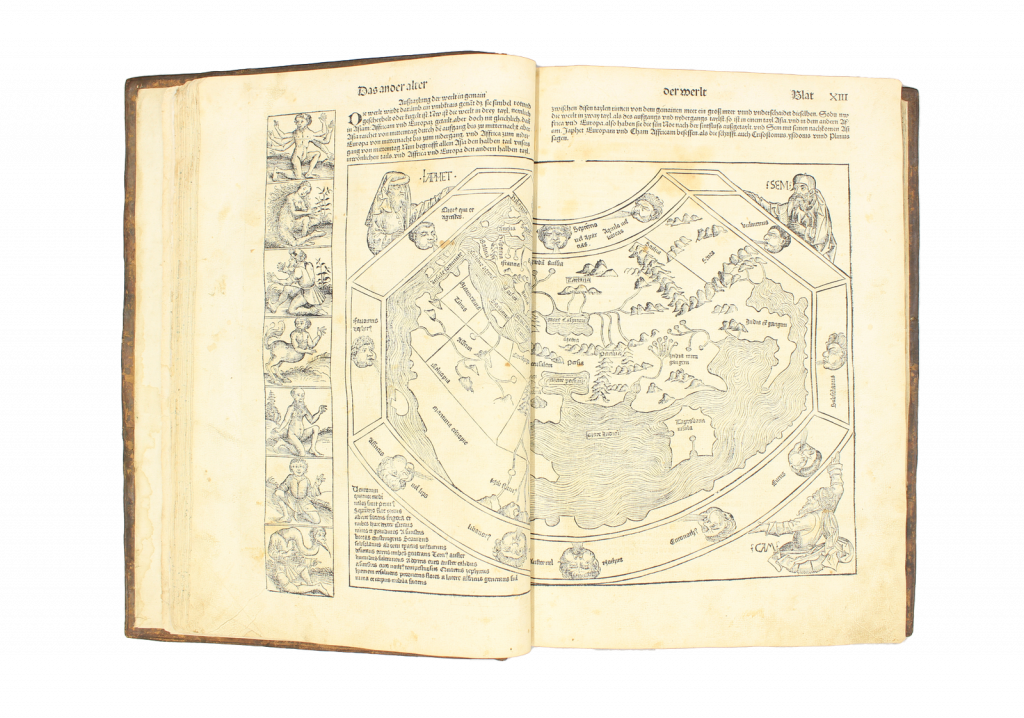

The very first Western European printed map of the world, of the so-called ‘T-O’ type, was printed in 1472 from a woodcut. This type, however, are little more than diagrams, with a minimal amount of geographic detail or information.

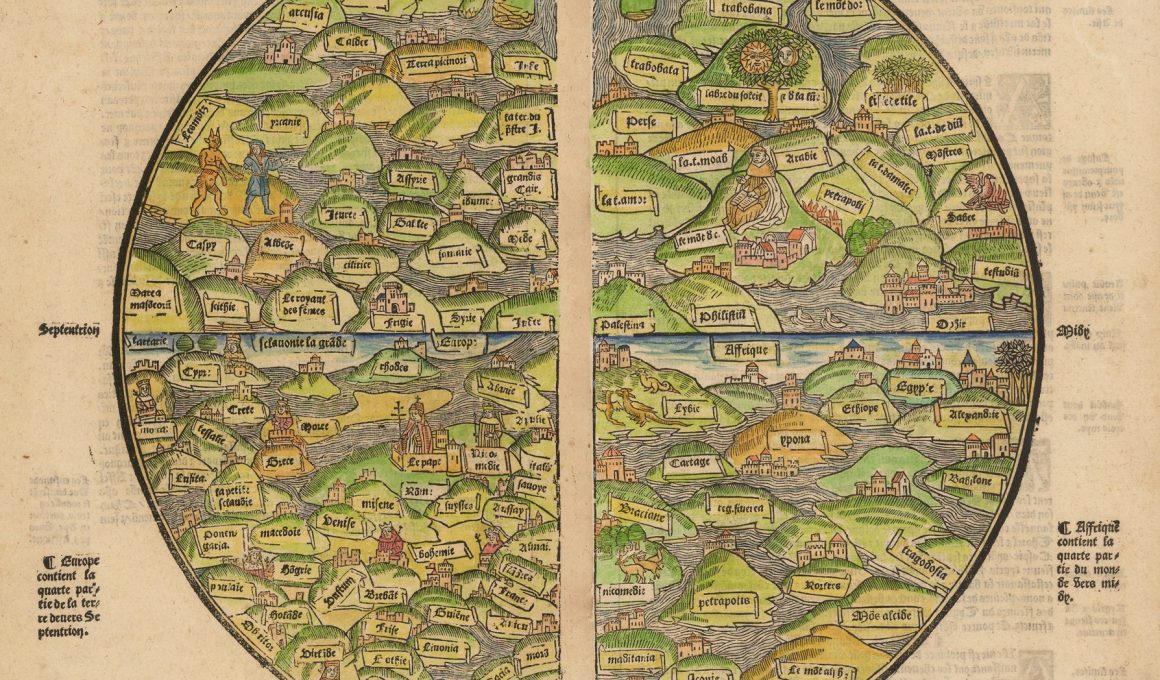

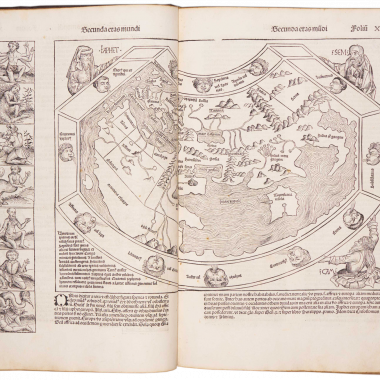

The first printed maps worthy of that title were published in the Rudimentum Novitiorum (Lübeck, 1475). The two were a map of the World, and of Palestine. Both were woodcuts, printed from two blocks. The World map was, in its basis and design mediaeval, with the World compressed into the circular frame of the ‘T-O’ form. The world is portrayed in pictorial form; thus, the Pope can be seen in the lower left quadrant, enthroned in Rome, with the Pillars of Hercules positioned at the very foot, with Spain, and then the British Isles just above.

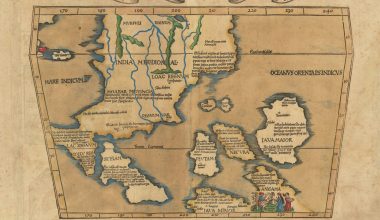

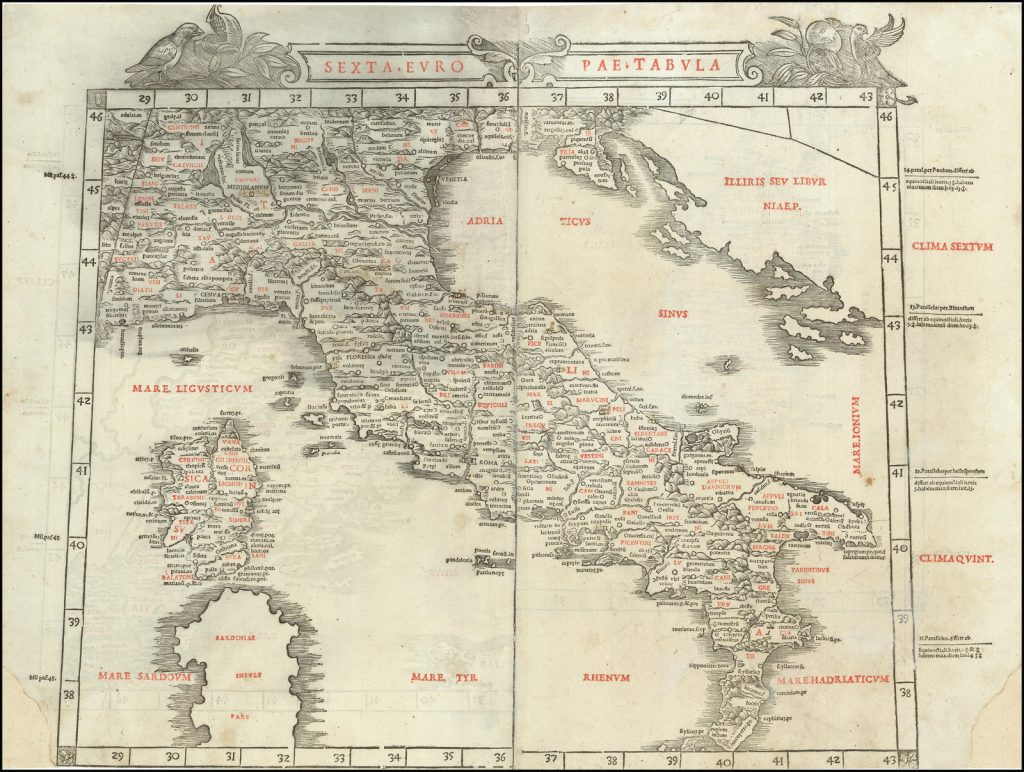

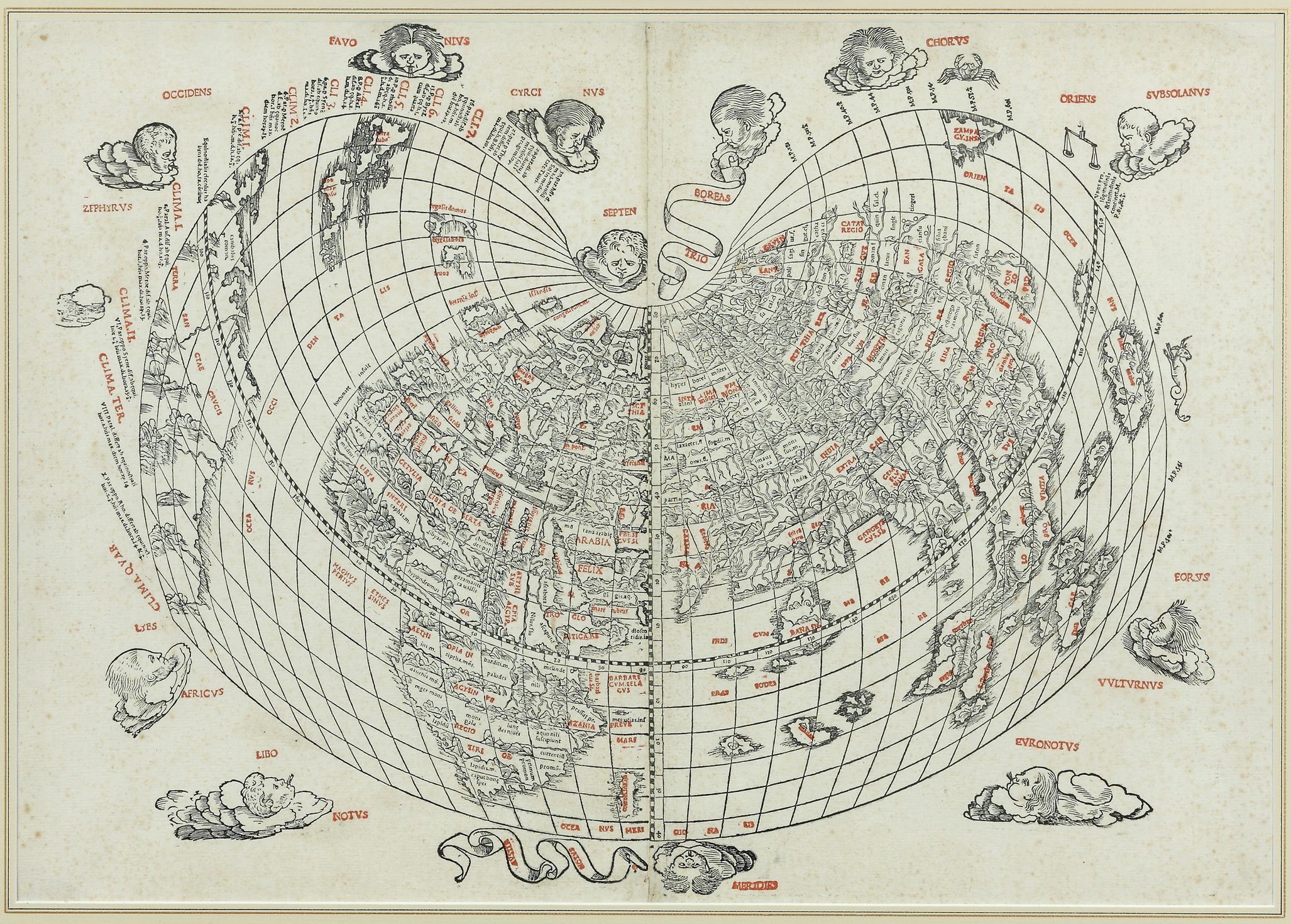

Of the four Ptolemaic world atlases published in the fifteenth century, the three Italian versions were printed from copperplates, the Ulm edition from woodcuts. The woodcuts in the Ulm Ptolemy are generally credited to Johannes ‘Schnitzer’ (“the woodblock-cutter”) from Armsheim. One characteristic of his work is that he tended to reverse his capital ‘N’s when cutting the letter. The next three Ptolemaic atlases published north of the Alps (Waldseemuller’s in 1513, Lorenz Fries’ in 1522 and Sebastian Munster’s in 1540) all used woodcut maps, and it was not until Mercator’s edition of 1578 that a series of copperplate maps appear.

Of the Italian editions of Ptolemy only one, that of Bernard Sylvanus, published in Venice in 1511, used woodcuts. All the others used copper engravings.

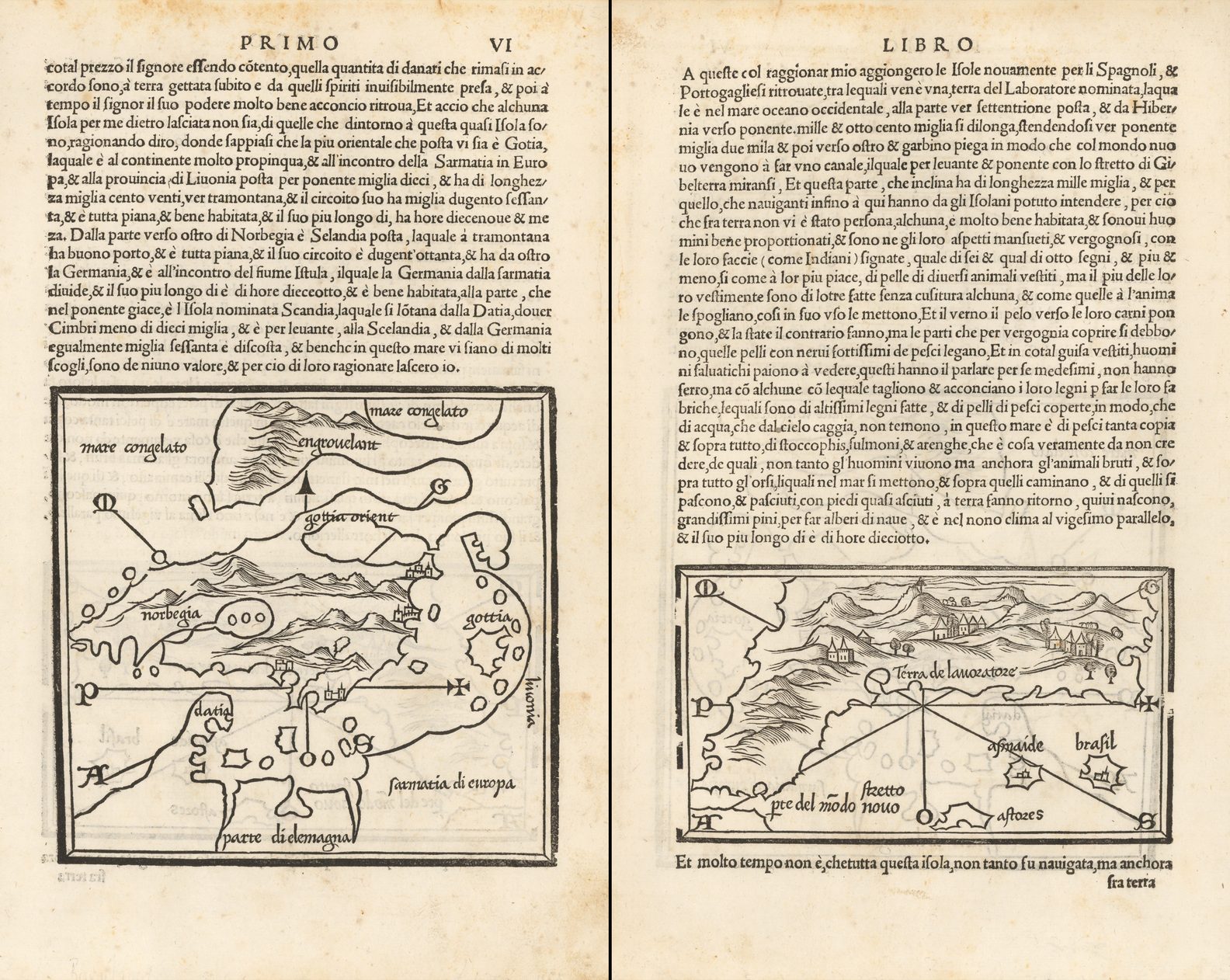

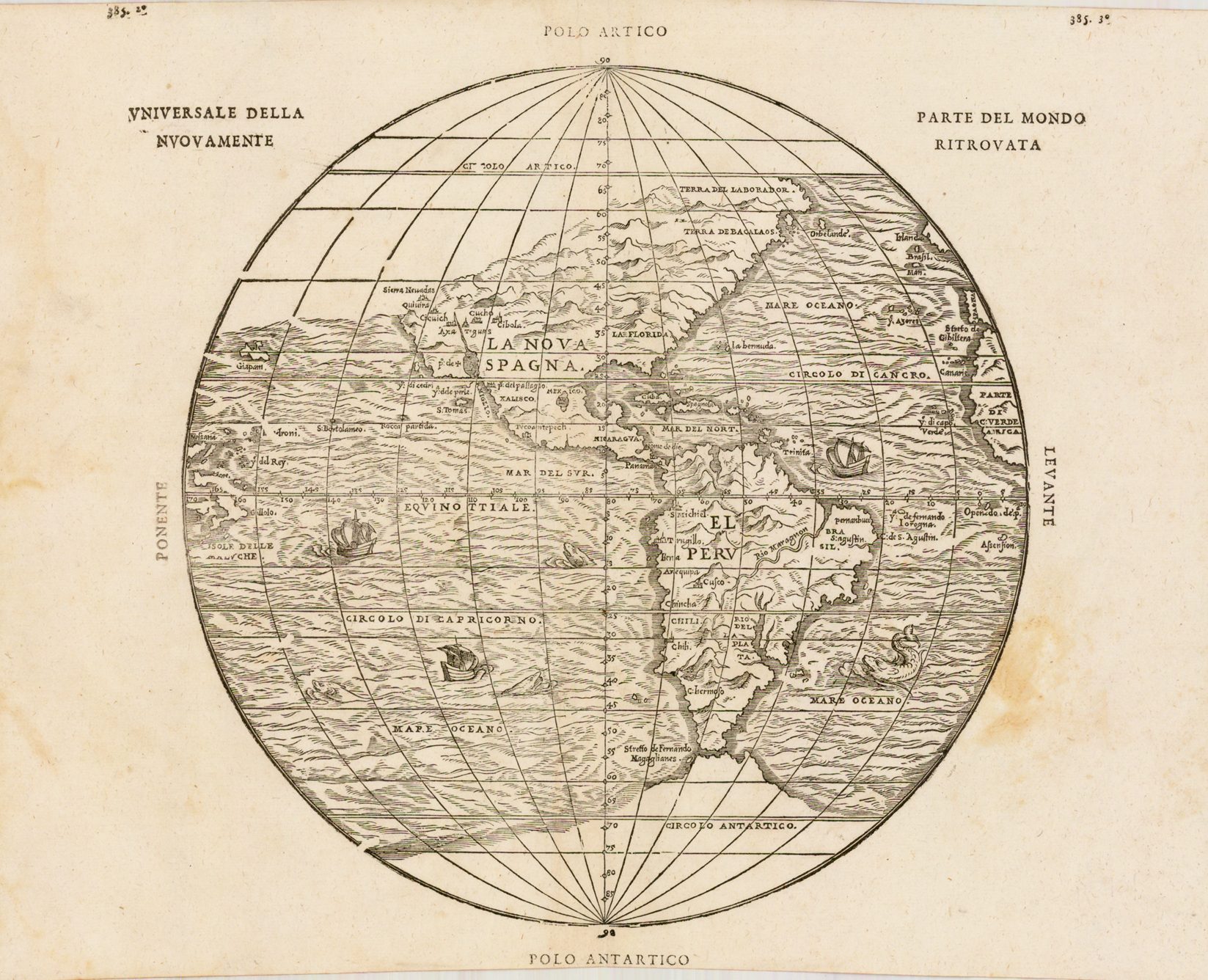

There are a small number of Italian books that used woodcuts maps. Among the most famous was Benedetto Bordone’s Isolario, Libro Di Benedetto Bordone Nel Qual Si Ragiona De Tutte L’Isole Del Mondo, first published in Venice in 1528, containing 111 woodcut maps and plans. Bartolommeo dalli Sonetti’s untitled book of the islands of the Greek archipelago, published in Venice circa 1485, contained 49 woodcut charts, each without any lettering within them. Two other rare Isolarii were prepared by Pietro Coppo. The first, known only in a unique manuscript, is his De Sum[m]a Totius Orbis…, accompanied by 15 woodcut maps, some dated between 1524 and 1526. The second was his Portolano…, published Venice in 1528, with 7 woodcut maps.

Two famous Italian mapmakers who worked in woodcut, issued a number of separately-published maps: Matteo Pagano and Giovanni Andrea di Vavassasore. Unfortunately, their output is rarely encountered today.

North of the Alps the use of woodcuts was popular in illustrated books, such as Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Cronicarum (Nuremberg, 1493), Sebastian Munster’s Cosmographia (Basle, 1544, onwards, with a new set of blocks cut in 1588) and François de Belleforest’s French copy La Cosmographie Universelle (Paris, 1575), Johann Stumpf’s Schwyzer Chronik (Zurich, 1547), among a host of examples.

The German school of cartography also used the woodcut for separately published maps, for example the output of Erhard Etzlaub, Martin Waldseemuller, Peter Apian, Philip Apian, and others. Early Dutch and Flemish publishers, such as Cornelis Anthoniszoon, Jacob van Deventer and Hieronymus Cock also employed this medium.

It is interesting to note that while German publishers north of the Alps favoured woodcuts, it was German printers and publishers in Italy that were responsible for overcoming the early difficulties experienced in preparing and printing from copperplates.

The Advantages Of Woodcuts

One of the principal advantages that woodcuts had over copperplates was that it was very much easier to combine a woodcut with letterpress text. While doing so with a copperplate involved two separate runs through the press, a page of text with a woodcut could be printed in one run, thus saving a great deal of time and effort. As a consequence, the vast majority of maps prepared for books in this period were printed from woodcuts.

A second advantage was that wood was very much cheaper to purchase than copper and – with one reservation – much easier to work with to create the image, unlike the considerable skill needed to prepare a copperplate. This meant that a woodcut could be completed much quicker than a copperplate, and by a less skilled artisan, so all the way round, production costs were less. Furthermore, the printing process was also easier.

Woodcuts were also physically more robust than copperplates. In general, they stood up to the tests and stresses of printing far better, and consequently could be used to print much greater numbers of maps than a copperplate.

The Disadvantages Of Woodcuts

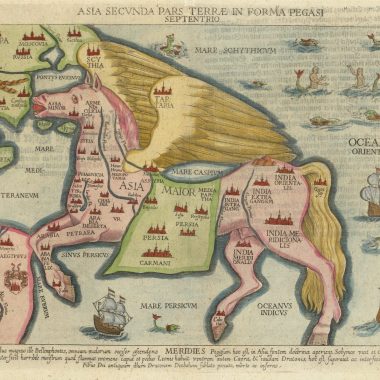

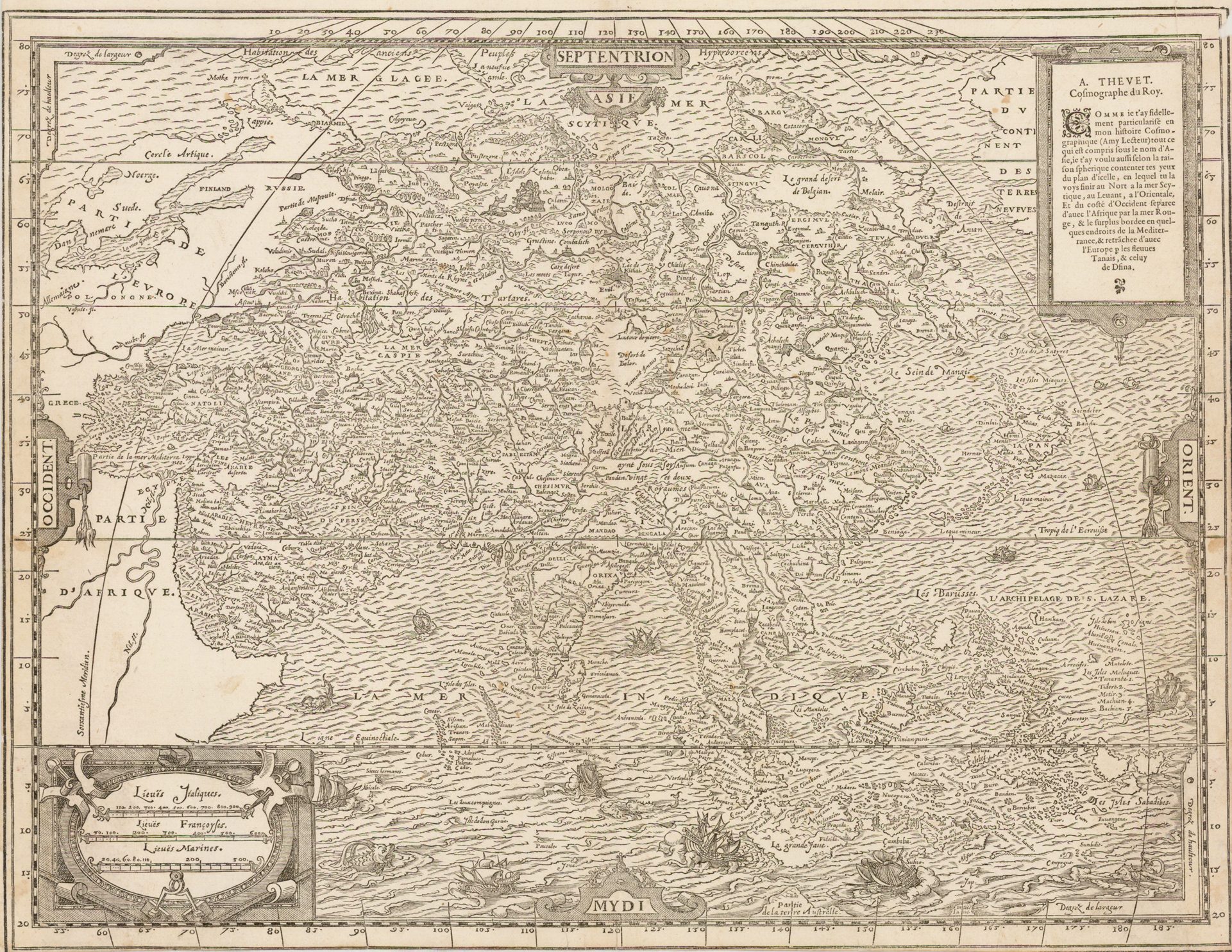

The principal difficulty with woodcuts was that the medium was very much cruder than copperplates. As examples of this, one might compare Ortelius’ copperplate maps of the Americas with woodcut copies of them, respectively by Andre Thevet from his Cosmographie Universelle (Paris, 1575).

While the modern audience might well appreciate the woodcuts for their greater sense of antiquity, woodcuts were simply not as good at conveying detailed geographical information as copperplates. Once a sufficient pool of skilled engravers existing, it is perhaps not surprising that woodcuts faded almost completely (but not totally) out of cartographic usage.

It was extremely difficult with woodcuts, for example, to introduce subtle shading to mark coastlines and the like. This may be one explanation of why the two Ulm Ptolemy editions (1482 and 1486) use such heavy hand-colouring for the sea, hills, and so on.

The main difficulty experienced by woodblock cutters, however, was lettering. It was very demanding to cut large number of names into the block, particularly where there was a high density of names. It is often a feature of woodcut maps that they have only limited numbers of place-names. Maps such as Thevet’s America represent considerable achievement on the part of the woodcutter.

There were a number of solutions, some less successful than others. Bartolommeo dalli Sonetti’s charts of the Greek islands (ca.1485) simply omit lettering altogether, with it being left to the purchaser, if he so wished, to insert names in manuscript.

The most commonly encountered solution was to use moveable type for major names, by inserting the type in recesses cut into the block for the purpose. The process was developed very early, with the two maps from the Rudimentum Novitiorum (1475) both having type lettering.

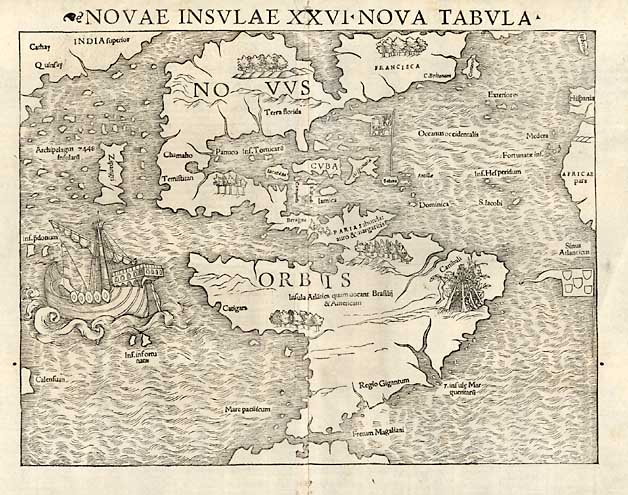

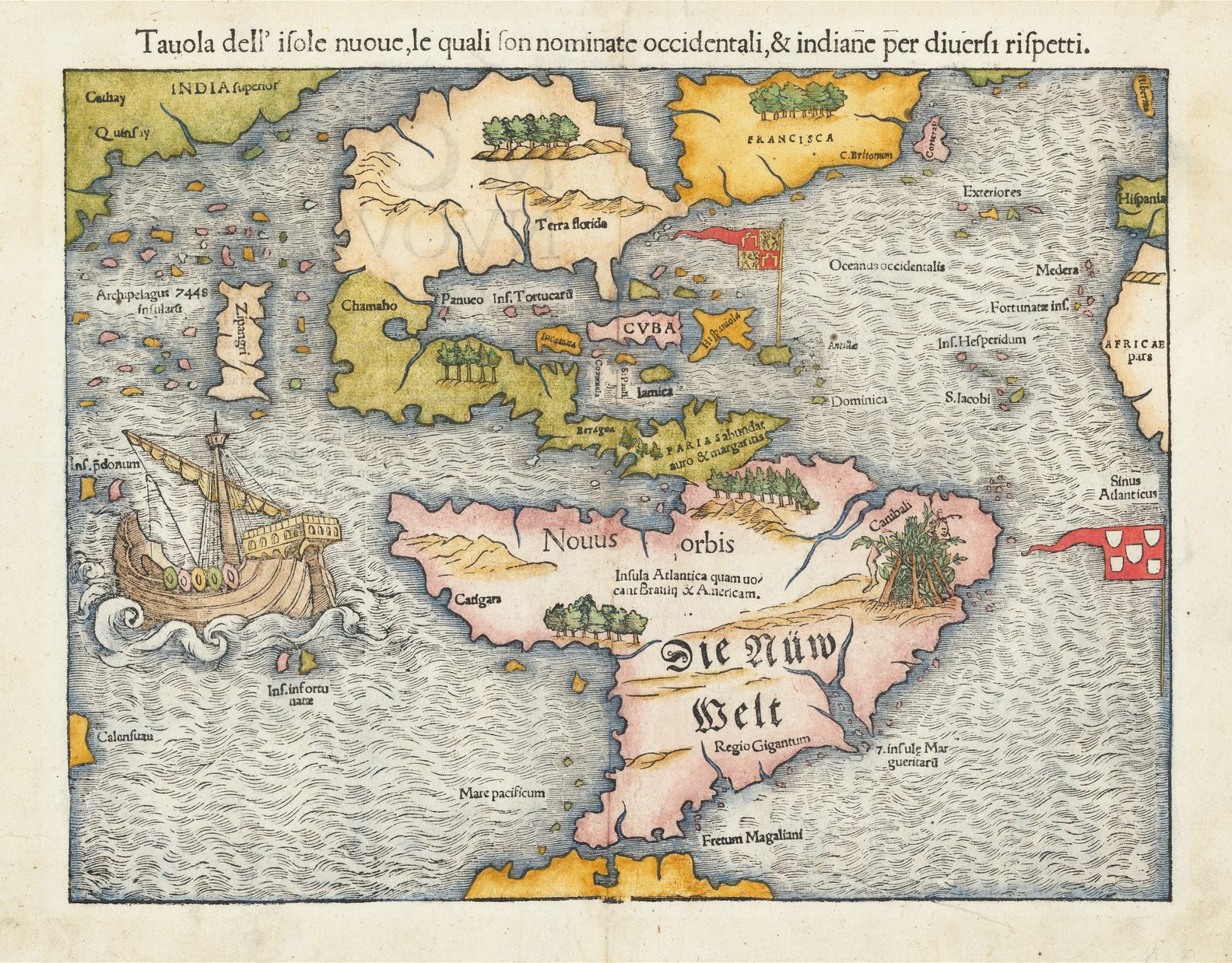

As this type could be altered or removed, it is possible to detect variations within maps, in relatively minor details in Grynaeus and Huttich’s map of the World (1532) or, more famously, in Sebastian Munster’s map of the New World (1540), where later issues have ‘Die Nüw Welt’ inserted in South America, and the two lines of text there rewritten. In some cases, publishers could even set the language of text panels, or heading above the map in the language of the book the map appeared in.

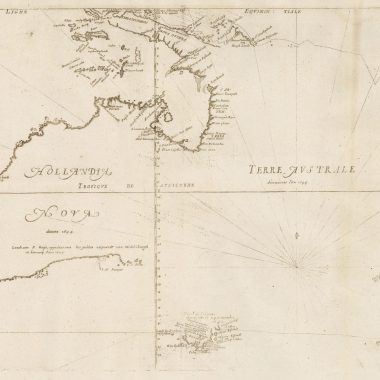

Another problem encountered by the publishers was that, in storage, the woodblocks provided an attractive source of nourishment for woodworm. The most famous instance of this was in the printing-house of the Giunti family in Venice, where woodworm attacked the blocks for Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s Delle Navigationi Et Viaggi. In the accompanying illustration, the damage done by the woodworm can be seen as blank tracks running through the lettering and shading, particularly in the left-hand border of the map.

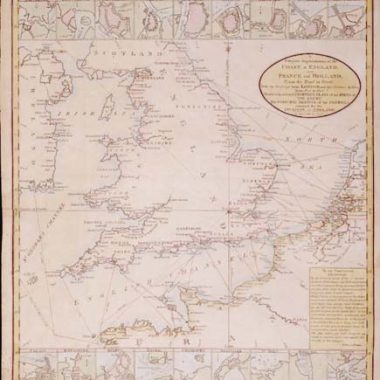

By the end of the sixteenth century, copper-engraving had established itself as the principal medium for preparing maps in western Europe. However, woodcuts did continue to appear, often in places where skilled engravers were in short supply – for example the British colonies in North America.

The first map ‘engraved’ and printed within the confines of the modern United States was a woodcut printed by John Foster to illustrate William Hubbard’s Narrative Of The Troubles With The Indians In New-England (1677). At the same time, an English edition of the book was planned – Present State Of New England. Being A Narrative Of The Troubles With The Indians In New England. For this edition, an example of the map was sent to London, so it could be copied for insertion in the book. What is interesting is that the English publisher, Thomas Parkhurst, had a new woodblock prepared, rather than commissioning an engraving. So far as I am aware, it is the only significant woodcut map to appear in England between 1640 and 1730.

In the 1730s, the woodcut enjoyed a revival in England, arising out of the popularity of periodicals such as The Gentleman’s Magazine and London Magazine. Woodcuts, with their low cost and comparative ease of production were ideal for such publications, most particularly to accompany articles on current events, such as battles or sieges.

In the 19th century, the principal illustrated journal of the period, the Illustrated London News, used an extensive range of wood engravings, but that is a story for a later date.

References.

Tony Campbell, The Earliest Printed Maps 1472-1500, (London: The British Library, 1987), p.11.