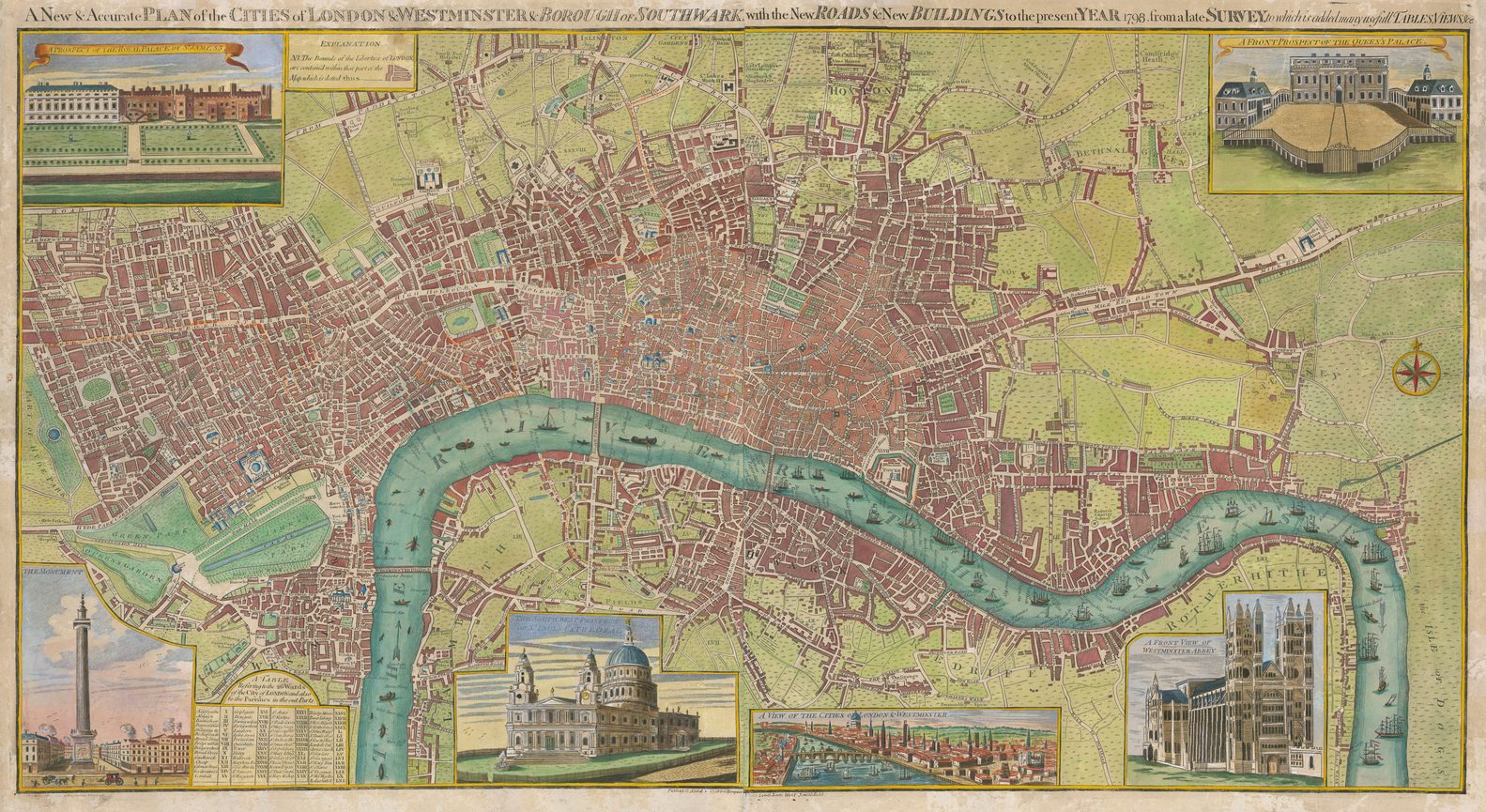

Although communications were a vital component of town growth and development, they rarely feature in maps of British towns. Even when communication facilities are recorded, they tend to be peripheral to the map’s purpose and are rarely delineated in any detail. Furthermore, the cartographic record of urban communication is almost solely confined to London.

It must be appreciated that London has always dwarfed all other British towns in importance. By the beginning of the eighteenth century London already had a population of about 600,000, about 30 times larger than either Bristol or Norwich which were the next largest towns. By 1800 London contained about one million inhabitants, between 10 and 20 times larger than any of its nearest rivals – Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester-with-Salford, and in Scotland Edinburgh and Glasgow. Even after the rapid industrialisation to the 1830s, only Birmingham, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester-with-Salford and Sheffield had over 7% of London’s population each and only another eight towns had approaching 4%. Thus, London had an extraordinary importance in the national economy due to its share of the country’s foreign trade, its function as a manufacturing centre and its demand for foodstuffs, raw materials and products from around the country and the world. London was and remained the largest retail market anywhere [1]. Inevitably, London’s commerce, size, share of national population and disproportionate share of the literate induced a development of urban communications which was barely imitated in other towns until the twentieth century [2].

The Post Office was founded in 1657. Postal services began as early as the seventeenth century when letters were carried by post-boys on horseback. By the end of the eighteenth century some 400 towns were receiving daily mail. However, the development of postal services was held back by the fact that charges were high, being dependent on the weight of the letter or packet and the distance travelled. Since it was the receiver of the mail who paid, delivery services were slow and sometimes recipients refused to pay. In some areas mail had to be collected from a receiving house.

By the 1670’s London had grown too large for the use of messengers whose services were replaced by a postal service between the various areas of the city. Initially, all letter of less than one pound in weight were charged one penny for the City and suburbs, and twopence for any distance within a ten-mile radius. Six large offices were opened in different parts of London and all the principal streets had receiving houses.

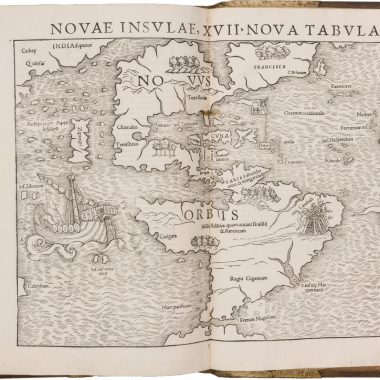

The ‘circuit of the penny post’ seems first to have appeared on the ‘accurate map of the country twenty miles round London’, published by John Fielding in 1782 and engraved by John Cary [3]. Cary continued his interest in postal delivery limits in London on his ‘new and accurate plan of London and Westminster, the borough of Southwark and parts adjacent’ (1787) [4], which was initially hand-coloured to show ‘Letter Carriers Walks’ [5]. The 1792 edition of the map was hand-coloured to delineate ‘Proposed Town Penny Post deliveries’ and a later issue to show ‘Present Town Penny Post deliveries’ [6].

The limits of the twopenny post delivery in London seem to have first been represented by Robert Rowe on his ‘map of the country twenty-one miles round London’ (1806) which shows the extent of the twopenny post by a red line [7].

The 1833 (?) edition of ‘Cary’s new plan of London and its vicinity’ [8] (1820) was ‘published by the authority of His Majesty’s Postmaster General’ ‘shewing the Limits of the Two-penny Post Delivery’. The ‘boundary of the two-penny Post Delivery’ is indicated by a ‘coloured Circle’ [9]. Cary’s map continued to be issued [10] under this authority until publication was taken over by George Frederick Cruchley [11] whose first issue of the map, c. 1851, still quoted the authority [12]. When reissued in 1857 the map had become ‘Cruchley’s new postal district map of London’ with the postal district boundaries added [13]. It was reissued in variants of this format until 1865 [14].

The Twenty-first report of the Commissioners of Revenue Inquiry (1830) included three maps delineating London’s postal delivery services. Aaron Arrowsmith engraved a ‘map shewing the several walks or deliveries in the country districts of the twopenny post…’ [15]; James Basire engraved the ‘map of London, shewing the boundaries of the general and two penny post deliveries the divisions or districts of the two penny post, and the number and situation of the general and two penny post receiving houses ‘ [16]; and Basire again mapped ‘the general boundaries of the general post delivery; of the foreign delivery; of the town delivery of the two penny post department; and of the country deliveries’ [17].

Similarly, the 9th Report of the Commissioners on Post Office Management (1837) contained maps, based on the Ordnance Survey, by James Wyld [18] portraying the changing limits of delivery. Wyld’s ‘map of the country 15 miles round London’ [19] showed ‘ by a yellow circle of 3 miles, the limits of the twopenny post delivery, by a blue line, the old limits of the three-penny post delivery, and by a black circle of 12 miles, the present limits of the threepenny post delivery’. The accompanying ‘map of London’ indicated ‘by the yellow line, the old boundary of the foreign letter carriers’ delivery. By the blue line, the old boundary of the general post letter carrier’s delivery, and by the black circle of 3 miles from the General Post Office, the present boundary of the general post delivery’ [20].

Wyld also produced a ‘Post Office plan of London‘ (c.1848-9) both individually [21] and as the central sheet of his Atlas of London & its Environs [22].

Until 1855 when they were amalgamated, the London District Letter-carriers existed as a separate establishment from the General Post. Consequently, the circular extent of the twopenny post delivery was still being added to its map of the ‘Environs of London’ in 1845 by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge [23].

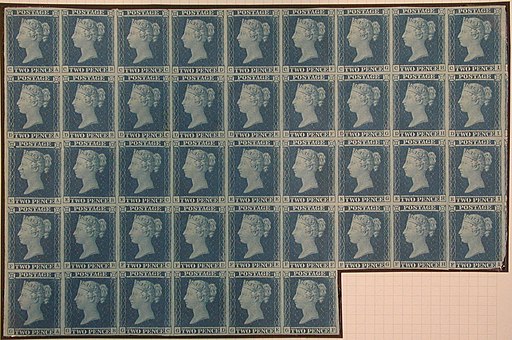

The inadequacies of the existing system were highlighted by Rowland Hill who believed that an industrial nation, such as Britain had become, needed good cheap communications to foster further development. He argued [24] that with a low standard rate of charge and prepayment by the sender, the whole population would be encouraged to use the system. Even with his suggested charge of one penny irrespective of distance, profits would increase due to increased business. Hill’s scheme was introduced in January 1840 and after mixed immediate results, the postal business was showing massive increases by the 1850s. By the 1870s the number of letters delivered had increased tenfold, with an annual average of 32 letters per head of population and almost double that by 1900, when nearly 2,000 million letters were dealt with per year. Books were carried from 1848, parcels from 1883, and picture postcards from 1894.

The coming of the penny post not only greatly extended communications between the growing urban areas, but also within them. By 1841, the 436 Post Receiving Houses in London were inadequate for the increased mail traffic. The first pillar-box was introduced in London in 1855 on the corner of Fleet Street and Farringdon Street, making it unnecessary to visit a post office in order to send a letter. The first map to show pillar-boxes appears to be James Dolling’s ‘Pocket Map of London’ (c.1862) [25] which locates them by black dots. In 1863 nearly half of all the letters delivered in London originated there [26]. By 1800 London had 2012 places of all kinds (post offices, sub-offices, letterboxes) at which letters could be posted, that is 7.5% of the whole for the United Kingdom.

London postal delivery limits continued to be shown occasionally on maps of the city and its environs after the introduction of the penny post. Richard Laurie mapped the area 12 miles round London in 1854, ‘being the limits of the Town Post Delivery’ [27]. Towns and villages have distances noted from the General Post Office with details of the number of dispatches and deliveries per day. Circles and squares also indicate distances from the Post Office. Similarly, Stanford’s great ‘Library map of London and its suburbs’ [28] (1862) also indicates ‘postal town delivery limits’. In July 1895 Kelly & Co. mapped the ‘collection & delivery boundaries for goods traffic’ of the Metropolitan Conference.

Post Office London Directory, 1915; via Kelly’s Directories Ltd

The number of Post Offices opened in the United Kingdom on the 31st of March 1880 was 912 head and 13,300 sub-offices. By 1880, the total number of places of all kinds (post offices, sub offices, letterboxes) at which letters could be posted in the United Kingdom was 26,753. Subsequent issues of the various post office directories, most notably Kelly’s, reveal the rapid increase in provision. Many such directories were accompanied by maps which, although not usually featuring postal information, were designed to provide postal address information [29]. P.J. Jackson & Co.’s Postal Address Directory of Carlisle (1880), for example, was illustrated by ‘P.J. Jackson’s new postal address map of Carlisle’.

‘Cary’s new pocket plan of London, Westminster and Southwark…’ [30] (1790) records ‘The situation of the Receiving Houses of the General & Penny Post Offices’. A table below the map records ‘ 2 Penny Post Receiving Houses. Chief Office in Throgmorton Street’, and one on the map face lists ‘Receiving Houses appointed by the General Post Office in Lombard Street’. The 1797 issue of the map replaced the City Office with the ‘Westminster Chief Office Gerrard Street’ and the ‘City Chief Office Abchurch Lane’. The 1797 edition of the plan was used to illustrate a survey of postal delivery undertaken in 1796 by Ferguson and Sparke [31].

Money orders were first suggested by Florence Nightingale as a means for soldiers to send money home from the Crimea. However, money order offices rarely feature on maps as a branch of the postal service. An early exception is Dolling’s ‘Pocket map of London’ (c. 1862) which, as well as locating pillar boxes, also identifies ‘post & money order offices’. Similarly, the ‘Picture map of Manchester and strangers illustrated guide’ (c. 1886) features ‘post and money order offices’ [32].

The telephone was invented in Canada by the Scotsman Alexander Graham Bell in 1876. It began to come into use in Britain in the 1880s, initially as a result of private initiative but later through municipal promotion. The first public telephones arrived in 1884. The National Telephone Company was formed in 1889 from the amalgamation of many private companies. However, through the extension of public control from the early 1890s, by 1912 the Post Office had become responsible for the telephone services of the entire country, with the exception of the local services in Hull, which continued as a separate undertaking.

The telephone did not really come into its own in Britain until the early 1930s. Although the National Telephone Company established an exchange in Cambridge, for example, in 1892, there were only 128 subscribers in the town by 1896. By 1910, there were only 122,000 subscribers nationally [33]. Although the telephone reached London in 1878 and the first exchange opened in Coleman Street in the City in 1879, there were less than 1000 subscribers within two years. However, by 1882 subscribers had the use of fifteen exchanges in the city [34].

Given such slow development of the urban telephone network, it is no surprise that there is virtually no cartographic record of telephone services in British towns, with the exception of isolated late examples of urban maps relating to telephone rates. The Daily Telegraph, for example, published its ‘new Telephone Rates Map of London & 25 miles round’ c.1921. This map was produced by ‘Geographia’ which was also responsible for the preparation of the ‘Liverpool Daily Post new telephone rates map of Liverpool & district produced under the direction of Alexander Gross…’ Telephone exchanges are located in red and the inner telephone charge zone of two miles round the town hall is marked. ‘Calls between all Exchanges in Inner Zone 1 1/2d. Calls between Exchanges within Inner Zone and Exchanges within Outer Zone (within 7 miles of Town Hall) 1 1/2d. Calls from any Exchange outside the Inner Zone to any Exchange within 5 miles 1 1/2d. For charges not covered by above see Diagrams and Table of Rates’.

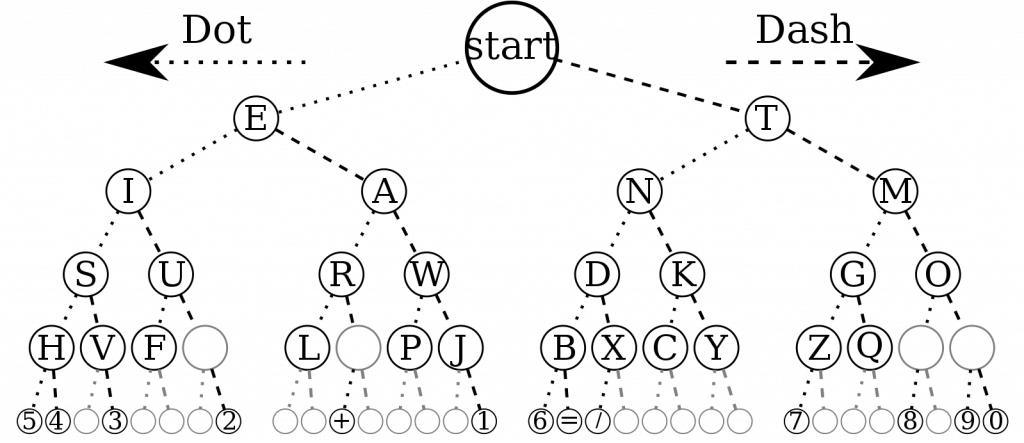

The electric telegraph was patented in Britain in 1837 following the pioneering work of Cooke and Wheatstone. In 1839 experiments were made along the Great Western railway line from Paddington to West Drayton, running the electric wire through iron tubes. However, early progress was slow due to the high cost of the system. The electric telegraph enabled messages to be sent along the wires, initially by needles tilted to indicate the different letters. This complicated, slow method of transmitting words was replaced by the simpler transmission of the ‘dot and dash’ code invented by Samuel Morse in 1838, which came into use c.1845 [35].

However, the expense of the telegraph system slowed progress. In 1846 the Electric Telegraph Company was formed. By 1854 it boasted 17 offices in the metropolitan area, of which eight were located at railway termini. After 1850, various private companies opened telegraph services and competition developed for business. Within a few years, most large towns were connected by telegraph, allowing urgent messages to be sent at the receiving office and delivered to their destinations. The telegraph wires, which ran alongside the railway lines, not only carried urgent personal and family communications but also urgent commercial intelligence and ever increasing national and international news for the press. The building of the telegraph system alongside the railways and the establishment of early telegraph offices at the stations created a natural association between the two in the map-maker’s mind and it was logical to combine railway and telegraph information on the same map. Thus, for example, Cruchley, in adapting Cary’s large county series [36] turned them into ‘Railway & Telegraphic’ maps [37] giving not only railway information but also details of telegraph lines and stations. While these maps are county maps rather than urban maps, they do at least identify towns with telegraph offices sited at the railway station. Similarly, Henry Collins adapted William Ebden’s county maps [38] to emphasise telegraph lines and telegraph offices ‘open daily only’ and ‘open day & night’ [39].

In 1868 all telegraph services were taken over by the Post Office. ‘At the time of transfer, the Telegraph Companies had 1,992 offices, in addition to 496 railway offices at which telegraph work was performed, making the total number of offices 2,488’ [40]. By 1880 there were 3,924 post offices and 1,407 railway stations open for telegraph work, ‘making the total number of telegraph offices within the United Kingdom 5,331’ [41]. Thus, urban maps locating post offices and railway stations [42] also, generally, incidentally locate telegraph offices.

Thus, the communications mapping of British towns is sparse in the extreme, being almost exclusively confined to London. Clearly, the development of communications was not considered to be of importance, interest or significance to the map-maker. For once, the maps of the British towns fail to be a significant source for the urban historian [43].

References

[1] For an extended discussion of the importance of London, see: Dyos, H.J & Aldcroft, D.H.: British Transport. An economic survey from the seventeenth century to the twentieth (1971).

[2] Inevitably, therefore, virtually no examples of pre-1914 urban communication mapping have been found for provincial towns. A survey of the printed map resources of the British Library’s Map Library has revealed only those maps featuring communication here discussed.

Full carto-bibliographical details of maps of the whole of London are given in:

Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: The Printed Maps of London c. 1553-1850 (1964; reprinted 1978 with revisions and additions)

Hyde, R.: Printed Maps of Victorian London 1851-1900 (1975)

[3] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit. no.174.

For details of John Cary and his work, see: Fordham, Sir H.G.: John Cary. Engraver, Map , Chart and Print-Seller and Globe-Maker 1754 to 1835 (1925), Smith, D.: ‘The Cary family’ (Map Collector, 43; 1988), and Smith, D.: ‘John Cary’ (Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement: Missing Persons; 1993)

[4] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit. no. 184.

[5] British Museum: London. An excerpt from the British Museum Catalogue of Printed Maps, Charts and Plans. Photolithographic edition to 1964 (1967).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit no. 239.

[8] Fordham, Sir H.G. : op cit.

Darlington, I. & Howgego, J. : op cit, no. 279 does not record Fordham’s edition of 1833, noting no editions between 1831 and 1835 which was ‘published by authority of His Majesty’s Postmaster General’ ‘shewing the Limits of the Two-penny Post Delivery’.

[9] Hackney coachmen were ‘allowed by the New Act of Parliament to charge back Fares from all places outside the same Circle’.

For discussion of maps giving details of hackney coach fares and other cartographic aspects of urban road transport see: Smith, D. : ‘The mapping of British urban roads and road transport’ (Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 30,1;1996).

[10] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit, no. 279 records editions of the 1835, 1836, 1837, 1838, 1845.

British Museum: op cit, records an edition of 1841.

[11] For details of Cruchley and his reissue of Cary’s works, see: Smith, D.: ‘George Frederick Cruchley’ (Map Collector, 49; 1989)

[12] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit, no. 279 (1).

[13] Ibid. no. 279 (5).

[14] Ibid. no. 279 (10).

[15] Ibid. no. 323

[16] Ibid. no. 324.

[17] Ibid. no. 325.

[18] For details of Wyld see:

Smith, D. : ‘The Wyld family firm’ (Map Collector, 55; 1991)

Smith, D. : ‘The Wyld family firm. Further comments’ (Map Collector, 57; 1991)

Smith, D. : ‘The interpretation of cartographic imprints: the case of the Wylds’ (International Map Collectors’ Society Journal, 68; 1997)

[19] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: no. 364.

[20] Ibid. no. 365.

[21] Ibid. no. 416.

[22] Ibid. no. 415.

[23] Ibid. no. 339 (2).

[24] Hill, R.: Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability (1837).

[25] Hyde, R.: op cit. no. 79.

[26] Vincent, D.: ‘Communication, community and the State’ in: Emsley. C. & Walvin, J. (eds): Peasants & Proletarians, 1760-1860: Essays presented to Gwyn A. Williams (1985)

[27] Hyde, R.: op cit. no. 35.

[28] Ibid. no. 91.

[29] For discussion of the development of maps associated with post office and other directories, and the general mapping of communications, see: Smith, D.: Victorian Maps of the British Isles (1985).

[30] Darlington, I. & Howgego, J.: op cit. no. 192; for further details see Fordham, Sir H.G., op cit, no.2.

[31] Ferguson, H & Sparke, J. The several Divisions and Districts of the Inland Letter Carriers, showing the order in which each District is served, being the result of a Survey taken in the year 1796, for the purpose of ascertaining the most expeditious mode of delivery (1797).

[32] Published by Hale and Roworth, 45, King Street, Manchester.

[33] Waller, P.J.: Town, City & Nation. England 1850-1914 (1983)

[34] Barker, F. & Jackson, P.: London. 2000 years of a city & its people (1974)

[35] On 1st January 1845, a suspected murderer was seen boarding the Paddington train at Slough. The telegraph office at Paddington was alerted. The suspected murderer, John Tawell, was arrested on arrival. Thus, the speed of the electric telegraph was most effectively demonstrated.

[36] Cary’s new English atlas; being a complete set of county maps, from actual surveys … on which are particularly delineated those roads which were measured by order of the Right honourable the Postmaster-General, by John Cary …. (1809).

[37] Cruchley retitled the county maps c.1855; e.g. ‘Cruchley’s railway map of …, showing all the railways & names of stations, also the telegraph lines & stations …’ The maps were issued individually, sometimes under the cover title ‘Cruchley’s modern railway and telegraphic county map’. The maps were issued collectively c.1858 as Cruchley’s railway and telegraphic county atlas of England and Wales and subsequently both individually and in atlas until c.1900.

[38] For discussion of the early publication history of these maps, see: Smith, D.: ‘The early issues of William Ebden’s county maps’ (Imago Mundi, 43;1991)

[39] Henry George Collins first re-issued these county maps c.1853 as The new British Atlas containing a complete set of maps of the counties of England and Wales, with all railroads, telegraph lines, and their stations. The whole carefully revised. Signs for telegraph and telegraph stations ‘open day only’ and ‘open day & night’ had been added to the maps lithographically. The maps were sold individually from c.1858, sometimes under the cover title ‘Collins’ railway & telegraph map of …’ At about the same date the map titles were altered to ‘Collins’ railway and telegraph map of …’

[40] Report of the Postmaster-General for the year 1880.

[41] Ibid. ‘On taking over the telegraphs, the Post Office commenced with 5,651 miles of telegraph line, embracing 48,990 miles of wire, and these numbers have been increased to 23,156 miles of line, embracing 100,851 miles of wire. The total length of submarine cables connecting different parts of the United Kingdom was 139 miles in 1869; last year it was 707 miles…’

[42] For a discussion of the portrayal of railway station on urban maps, see: Smith, D.: ‘The railway mapping of British towns‘ (Cartographic Journal, 35, 2;1998)

[43] For discussion of urban maps as sources of other types of historical information, see:

Smith, D.: ‘The enduring image of early British townscapes’ (Cartographic Journal, 28, 2;1991)

Smith, D.: ‘Inset town plans in large-scale maps of Great Britain’ (Cartographic Journal, 29, 2;1992)

Smith, D.: ‘Public health and large scale mapping’ (Modern History Review, 4, 3; 1993)

Smith, D.: ‘Cholera and the medical mapping of English towns’ (Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 27, 1; 1993)

Smith, D.: ‘Public health and the large-scale mapping of British towns’ (International Map Collector’s Society Journal, 56; 1994)

Smith, D: ‘The earliest printed maps of British towns’ (Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 27, 2; 1994)

Smith, D.: ‘The preparation of the town plans for Lysons’ Magna Britannia’ (Cartographic Journal, 32, 1; 1995)

Smith, D.: ‘The mapping of British urban conditions, characteristics and social provision’ (Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 29,2;1996)

Smith, D.: ‘The leisure mapping of British towns’ (Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 31, 1; 1998)

Smith, D.: ‘British urban mapping of waterways, canals and docks’ (Cartographic Journal, 35, 1; 1998)