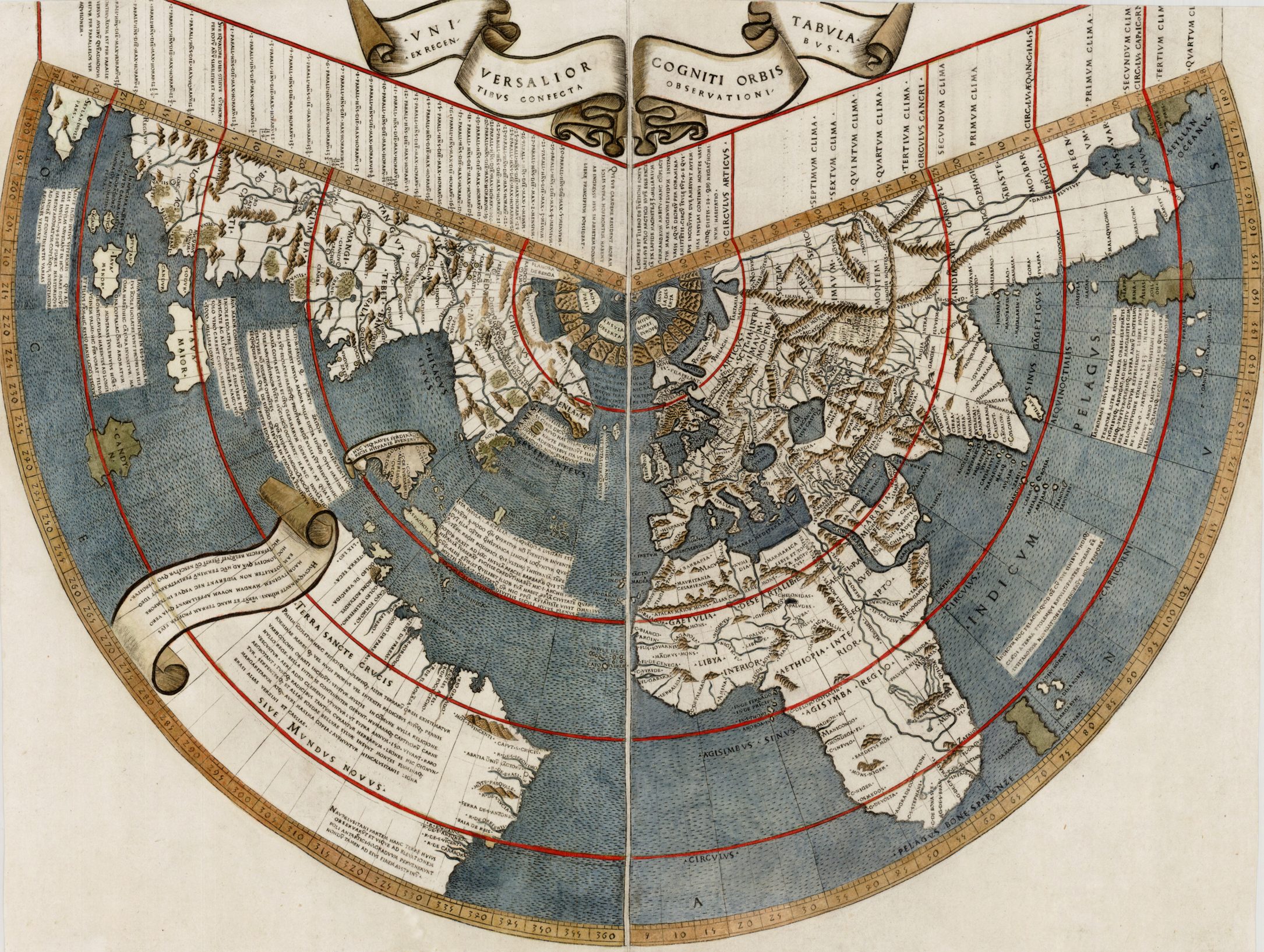

The earliest printed atlases were editions of the geographical text of Claudius Ptolemy (or Ptolemaeus), a Greek astronomer and geographer working in Alexandria, circa 150 A.D. Frequently accorded the accolade the “Father of Geography”, Ptolemy’s text dominated geographical study, in both the Christian and Muslim worlds, for over fifteen hundred years.

At the time that Ptolemy was working, Alexandria was home to the greatest library the world has ever seen, and also an important trading centre and cross-roads on routes between west and east. This later fact was an important factor in the growth of the library, for the Pharaohs ordered that travelers should have any books they were carrying confiscated, so that they could be copied. When the copy was completed, the original was deposited in the library, and the copy was given to the unfortunate traveller.

Thus, Ptolemy was in an excellent position to study existing geographical text-books and so on, which he could compare with contemporary travelers’ reports, and by consulting with merchants and travelers, as they passed through Alexandria.

From this wealth of accumulated knowledge, Ptolemy wrote two important books, the Almagest, a manual on astronomy, and the Geographia, a summary of knowledge on geography and map-making.

While not the first to write on these subjects, Ptolemy’s particular contribution was to try to apply a rigorous, scientific approach to gathering his information, and then in organizing and presenting the materials, which sets his work apart from previous writers. The most important of his methods was to use latitude and longitude co-ordinates to establish the position of the places mentioned, with some 8,000 locations listed in the text, indeed he may have been the first to use the terms “latitude” and “longitude”. Obviously, his work was handicapped by the difficulties of obtaining accurate data, but the underlying principle was a fundamental advance for cartography.

Such was the importance of Ptolemy’s work, and the wide influence it held over future geographers, that many of his errors were perpetuated by subsequent mapmakers. The most important of them was a miscalculation of the circumference of the earth. The circumference of the Earth was first determined by the Greek cosmographer Eratosthenes, from astronomical observations, circa 250 B.C., to be 252,000 Egyptian stadia. While the exact length of a “stadium” is not known, a total of about 26,400 statute miles is often cited (the actual circumference is 24,900 miles).

Ptolemy, himself, under-exaggerated the circumference if the earth, by calculating each degree of longitude as 500 stadia, instead of a more accurate 700 stadia. He then exaggerated the length of the Mediterranean by about 30%, and also that of Asia, thus greatly reducing the distance between the western tip of Spain, and the east coast of Asia. This had important consequences, as Tony Campbell noted:

Columbus, who owned copies of … the 1478 edition of Ptolemy, believed, or pretended to believe, that only 750 leagues (probably about 2,400 nautical miles) separated Lisbon from Cathay. Had Columbus known that the true figure was nearer 10,000 nautical miles, it is conceivable he would never have set out on his first, momentous voyage

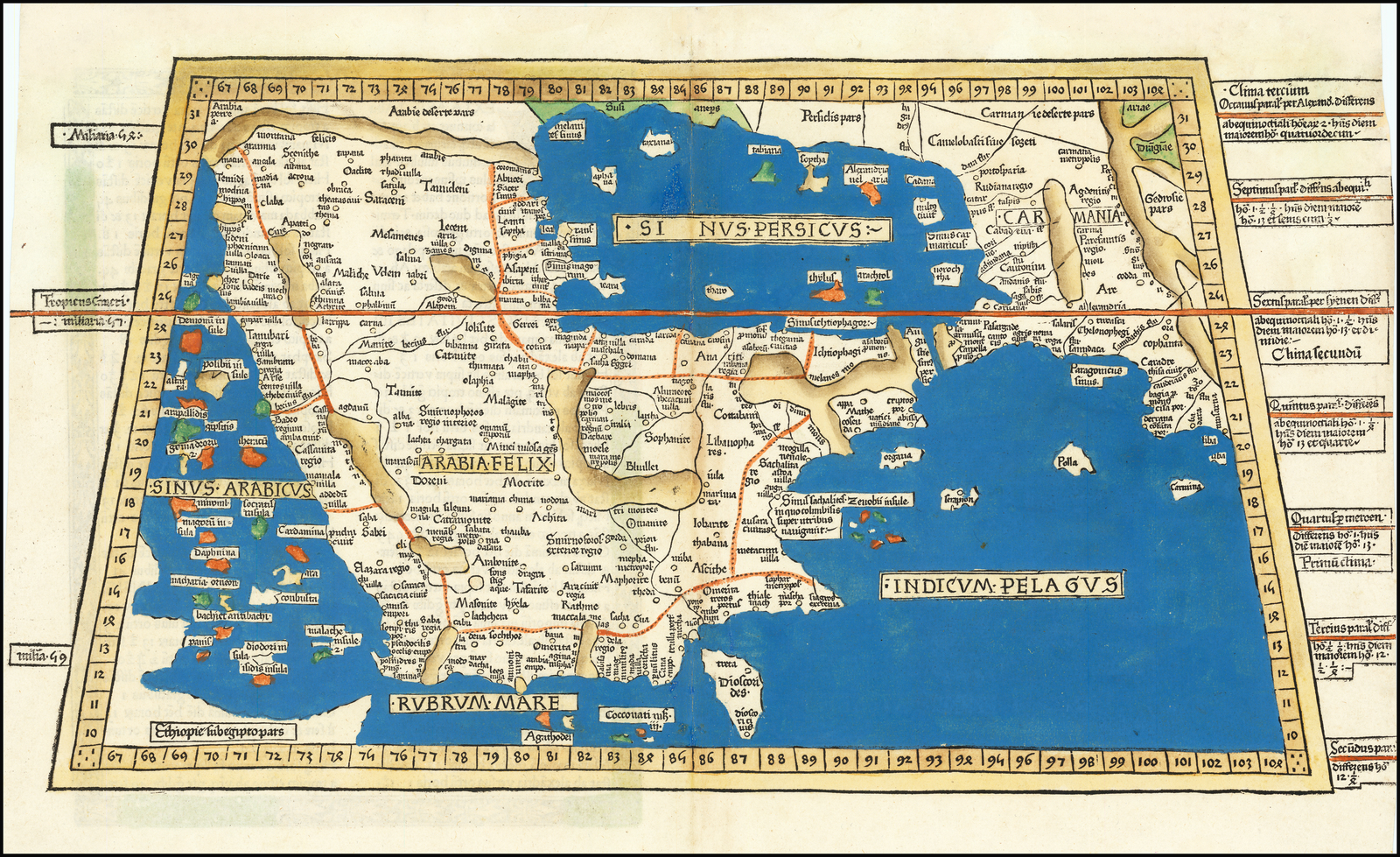

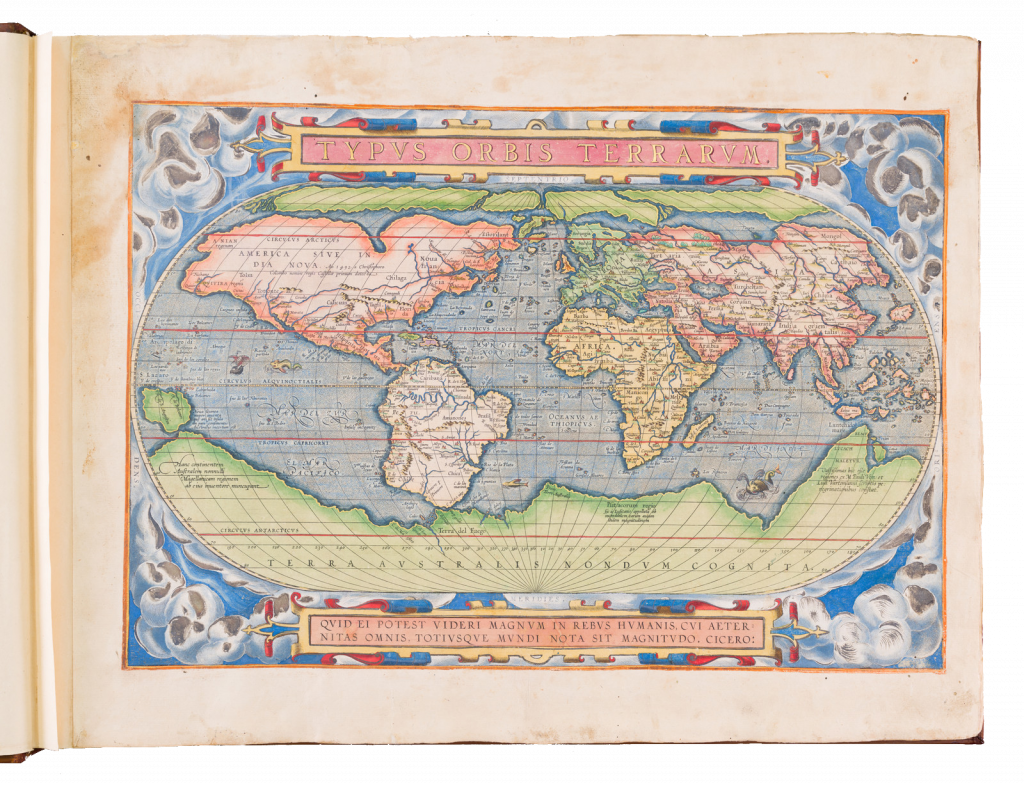

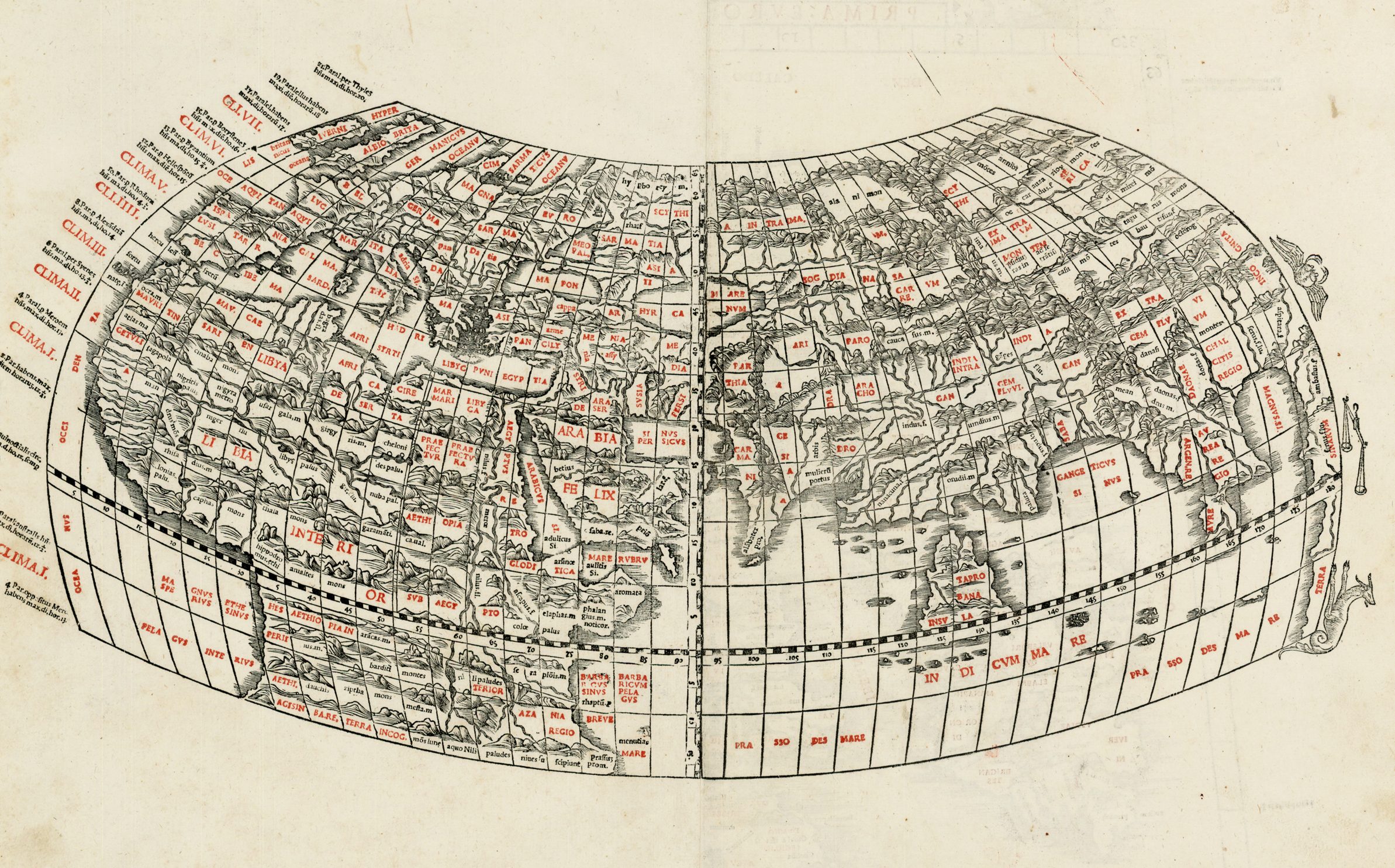

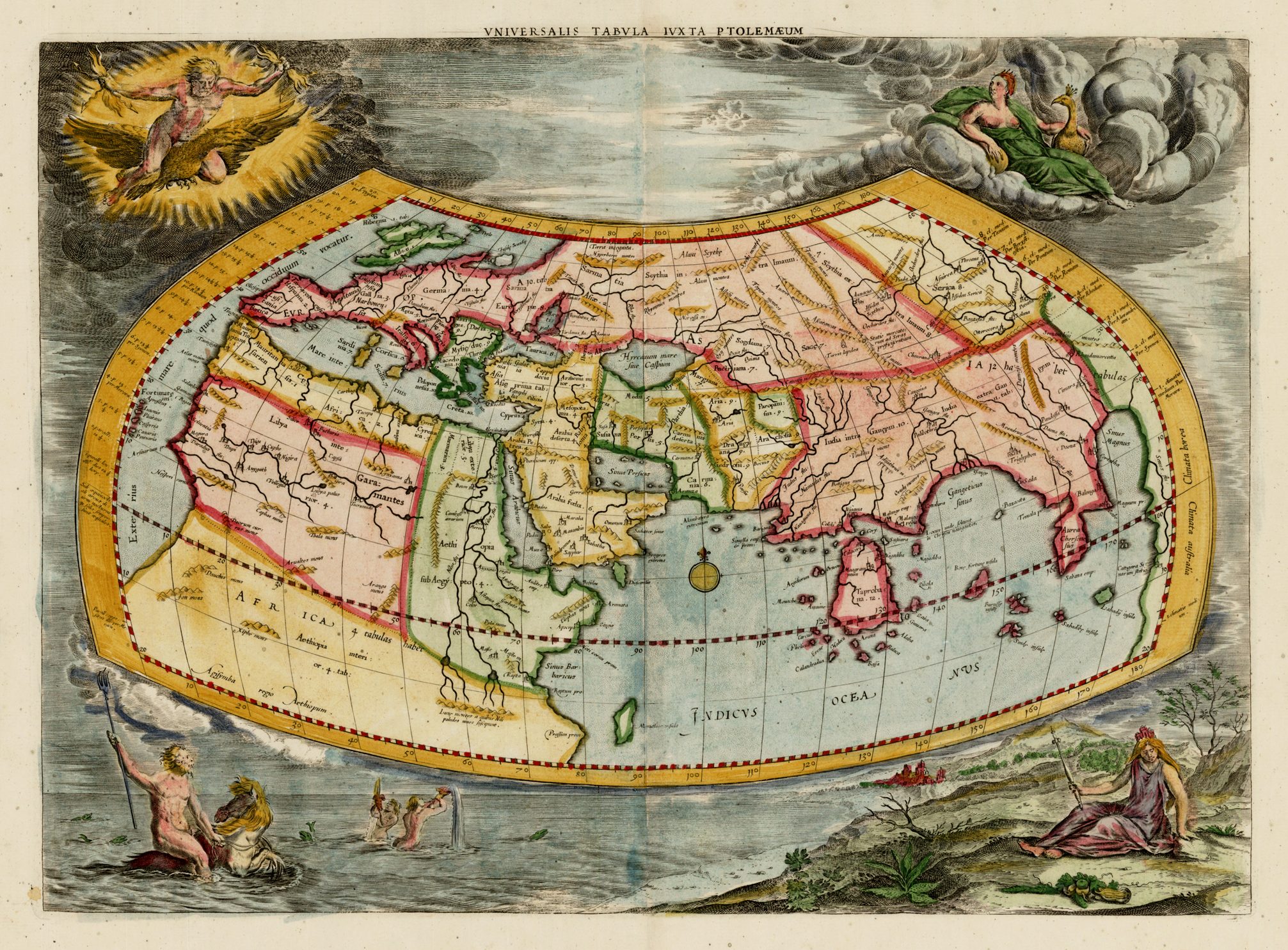

Another of Ptolemy’s errors was a belief that a southern continent existed, which counter-balanced the weight of the land-masses in the northern hemisphere, to keep the earth stable on its axis. This belief can be seen in the world map, where the southern continent forms a continuous land-link from Africa to South East Asia, with the Indian Ocean landlocked.

In the text of the Geographia, Ptolemy discussed the principles of Geography, introducing the subject thus –

Geography is a representation in picture of the whole known world with the phenomena which are contained therein … It is the prerogative of Geography to show the known habitable earth as a unit in itself, how it is situated and what is its nature; and it deals with those features likely to be mentioned in a general description of the earth, such as the larger towns and the great cities, the mountain ranges and the principal rivers. Besides these it treats only of features worthy of special note on account of their beauty …

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, Ptolemy’s text was lost to western geographers but, fortunately, the original text was translated into Arabic, for distribution among Islamic scholars and geographers, and was thereby preserved. In fact, the earliest extant manuscript version of the Geographia is Arabic, and probably dates from the 12th Century. Subsequently, the text was translated into Greek, and circulated through the Greek World.

In about 1400 or a little later, a Greek manuscript came into the hands of the Byzantine scholar, Emanuel Chrysolaras, who was working in Italy. Chrysolaras undertook a translation of the text into Latin, which was subsequently completed by his pupil Jacopo d’Angelo, in 1406. Angelo’s translation was used as the basis for the many 15th century manuscript and printed versions.

There is, however, some debate as to whether the printed maps are engraved versions of original maps which were passed down with manuscripts of the text, or whether the maps were constructed at a later date, from Ptolemy’s text, by medieval Greek scholars, or fifteenth century European mapmakers. Contemporary scholarship seems more inclined to the latter conclusion, for example, Tony Campbell wrote:

Since the oldest Ptolemaic maps date only from the late thirteenth century, it is unlikely that Ptolemy actually compiled any of the maps that illustrate his treatise .. However, the very emphasis of the text would seem to confirm that Ptolemy was working with, and from maps, a view taken by Dr. Joseph Fischer.

It is known that the world map can be attributed to Agathadaimon, whose name is often found attached to the full set of maps. Although when he actually lived is uncertain, he probably worked circa 250 A.D.

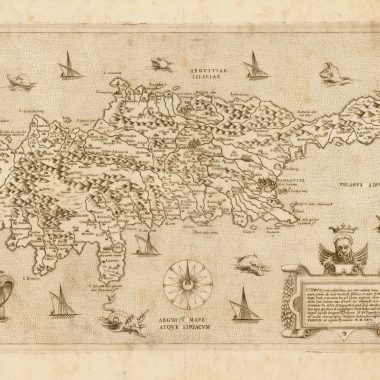

Whatever their origin, two different sets of maps are associated with manuscript versions of the Geographia – the so-called “A” and “B” groups. The latter consists of a map of the world and 64 maps of the Roman provinces. The former comprises a world map and 26 maps of countries, and it is this group that was the basis for maps in the printed editions.

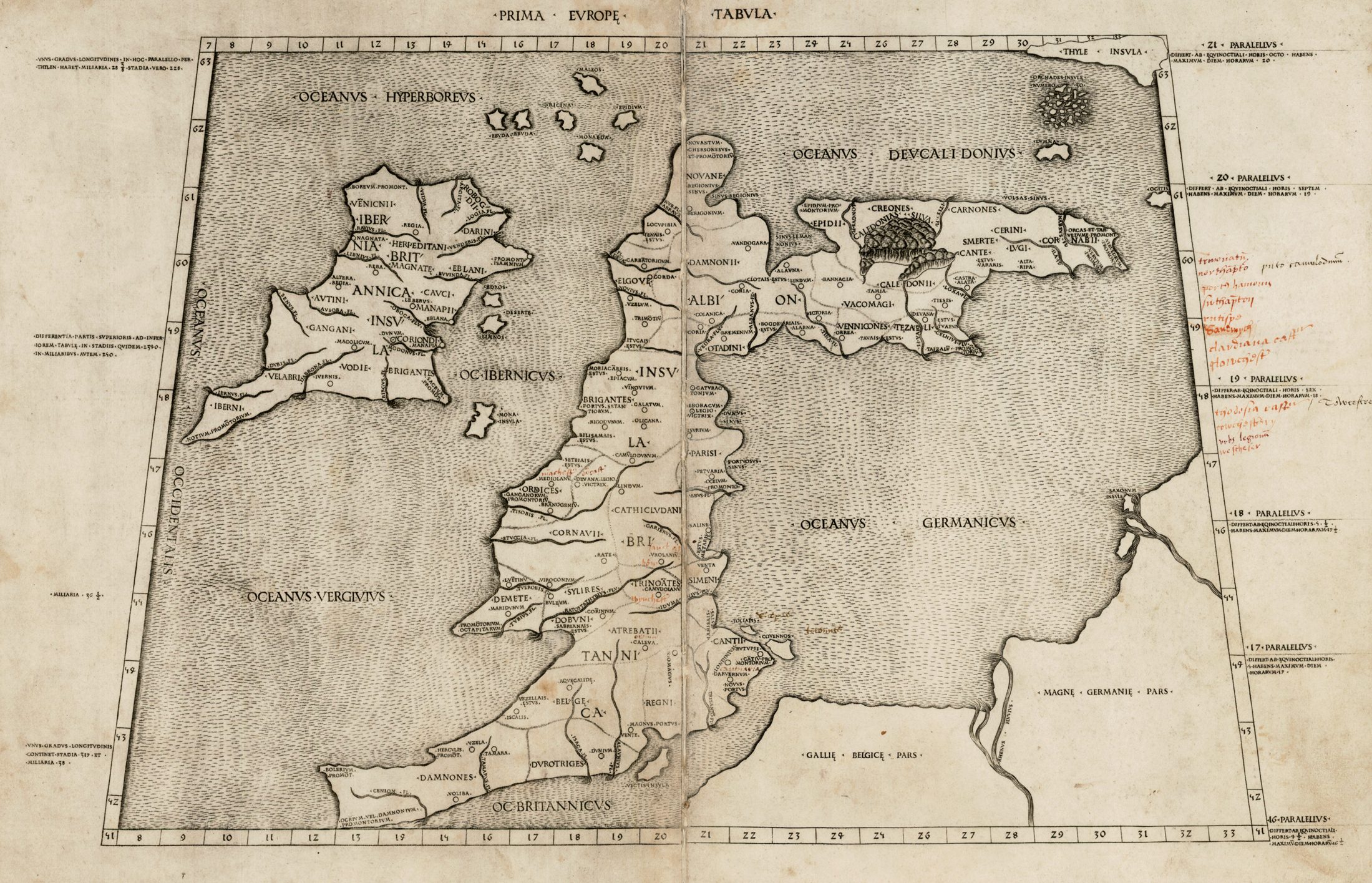

This group contained a map of the World, ten maps of parts of Europe (including separate maps of Britain, Spain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and Greece, for example), four of North Africa, and twelve of Asia (including a general map of the Levantine countries, Persia, Arabia, South East Asia, India and Ceylon).

The re-discovery of Ptolemy’s text created great excitement, and a large number of manuscript and printed editions were undertaken. The maps were far in advance of anything most people had seen, with the exception of the manuscript charts – portolani – devoted to the Mediterranean World, being produced in the principal sea-ports of Italy and Spain. Yet, Ptolemy’s maps depicted the World as it was known nearly fourteen hundred years earlier. While this may not have seemed so important in 1477, the limitations of the maps were exposed by the Portuguese discoveries in Africa, and Columbus’ crossing of the Atlantic, as Southern Africa, the East Indies, Japan and the Americas were wholly omitted from Ptolemy’s world view. These same limitations also apply to the maps of Europe, which retained out-dated perceptions, for example the west-east orientation of Scotland on maps of the British Isles.

Such was the impact of Ptolemy’s maps that, from 1477 to 1570, no terrestrial atlas was published that did not contain at its core his text and maps. Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published in Antwerp in 1570 was the first that was wholly composed of modern maps of the world and its regions.

The Greek manuscript that Angelo translated was apparently lacking maps, but the data in the text contained the information to construct a set of maps, and numbers of scholars set about such work. Of them, the most influential was Donnus Nicolaus Germanus, a German cartographer, active in Italy from the 1460’s to 1480’s. He was a prolific editor of the text and maps, and his work formed the basis for three of the four sets of Ptolemaic maps printed in the fifteenth Century, with the fourth, accompanying Berlinghieri’s Geographia, “strongly influenced” by him .

While a large number of manuscript versions of the Geographia were prepared in the course of the fifteenth century, the invention of printing, midway through the century, and its subsequent application to printing images, that enabled Ptolemy’s text to achieve the wide circulation it was to enjoy.

The first published edition of the Geographia with maps, which were probably engraved by Taddeo Crivelli, was issued in Bologna in 1477. Unusually, this edition contained 26 maps, with one of the Asia maps divided up among three neighboring sheets. With the exception of Palestine, these are the first regional maps of any of these various countries.

Unfortunately for the undertakers, this atlas seems not to have been a commercial success, and today only twenty-six examples of the atlas are recorded, with all but one in institutional libraries.

One explanation of the failure is that the publishers do not seem to have been fully mastered the intricacies and problems of engraving, and printing from, copper-plates, an art, which, after all, was very new and experimental. These problems were more successfully addressed by a German printer, Conrad Sweynheym, who was working on an edition of Ptolemy in Rome in the same period. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the volume appear, but his successor, Arnold Buckinck, saw the atlas through the press, in 1478.

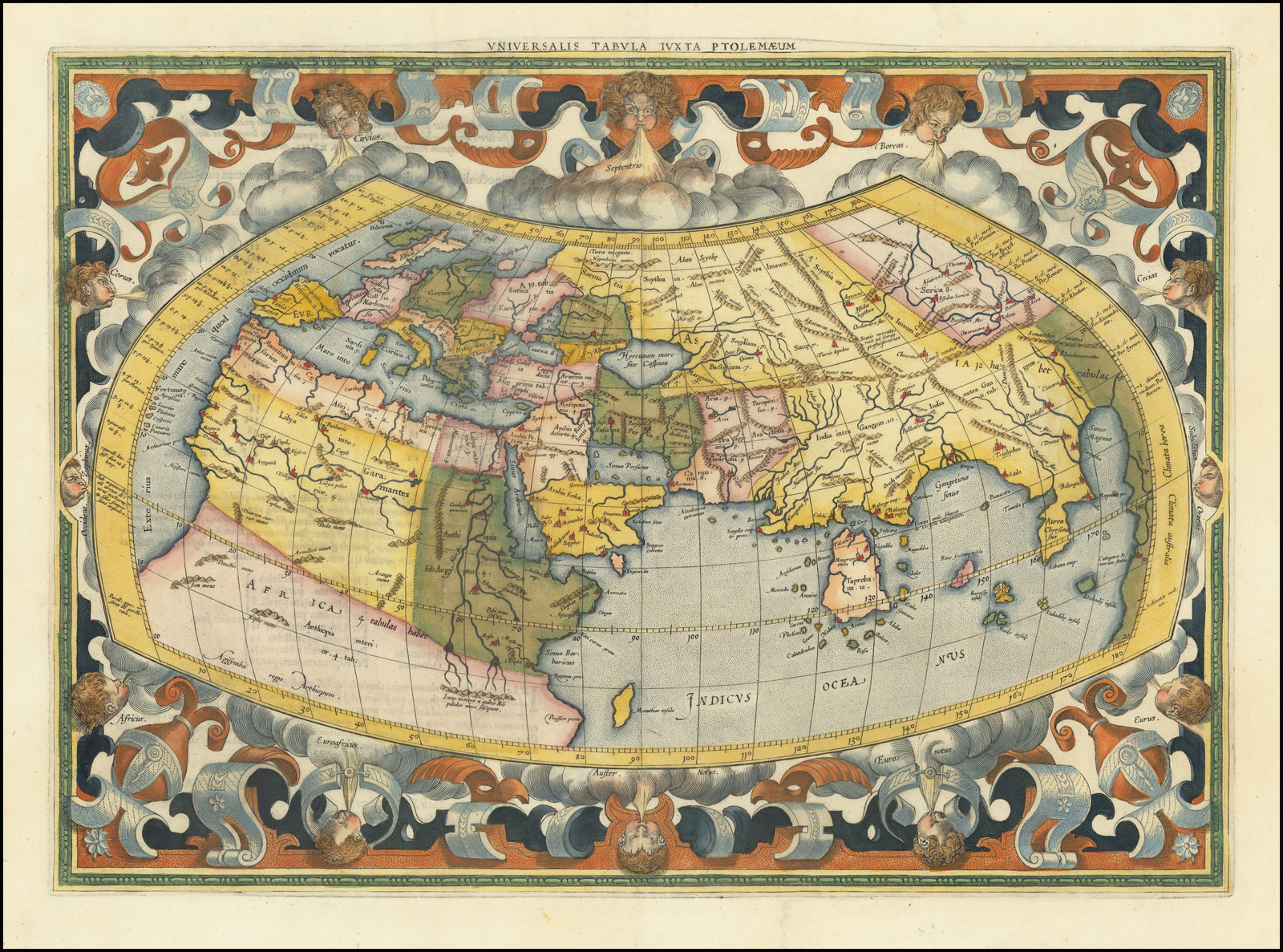

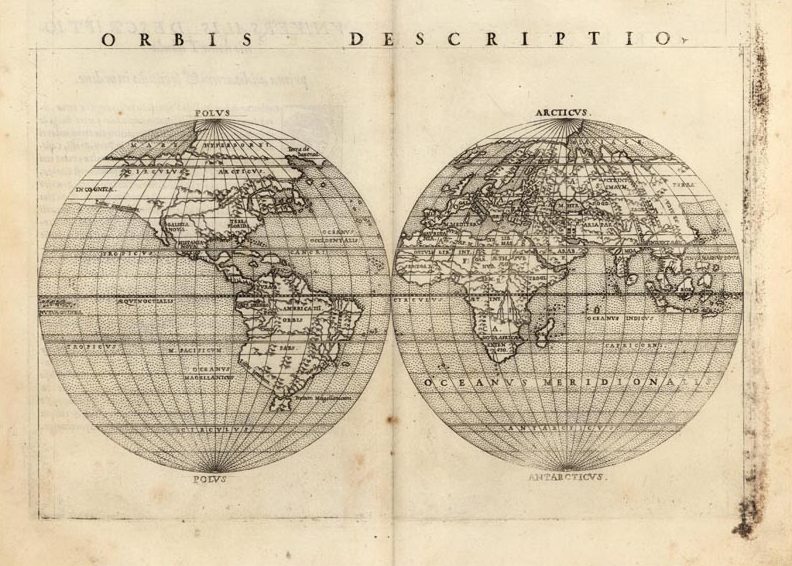

World Map from the 1478 Rome edition of Ptolemy’s Geography

The Rome Ptolemy contained 27 maps, with the same geographical coverage as the 1477 Ptolemy. Of the engraved editions of Ptolemy’s Cosmographia the maps in the Rome edition are the finest fifteenth century examples, and second only to Mercator’s maps, from his 1578 edition. One explanation for this was the use of individual punches to stamp letters onto the printing plates, rather than engraving them. This allowed much greater uniformity than lettering-engravers were able to achieve, and gives a very pleasing overall effect. The atlas proved popular, and three successive editions (to 1508) followed, although only about forty examples of the first edition are recorded today.

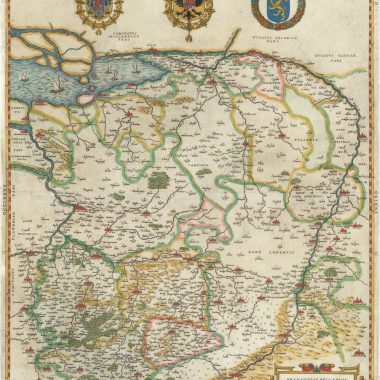

In 1482, Nicolas Laurentii published a set of Ptolemaic maps to illustrate Francesco Berlinghieri Geographia, a geographical description of the world, drawing on classical authors, augmented with more modern writings. The significance of the set of the maps is that it includes four supplementary modern maps, of Spain, France, Italy and Palestine, the first three the first modern maps of the respective countries.

The first edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia printed outside Italy was published by Lienhart Holle, in Ulm, also in 1482. Working independently of Berlinghieri, but apparently using the same or similar models, Holle also added modern maps of Spain, France, Italy and Palestine, but also the first printed map of Scandinavia, composed by Cornelius Clavus, circa 1425-7. Holle’s maps were printed from woodcuts, and are characterised by heavy wash colouring for the sea areas, typically a rich blue for the 1482 edition, and an ochre for the 1486 edition. These bright colours, and the greater sense of age that woodcuts convey, make this series the most visually appealing of these various sets of maps.

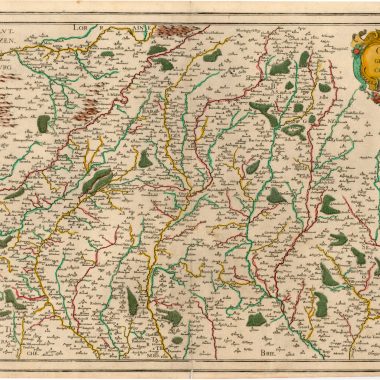

For the 1507 (third) edition of the Rome Ptolemy, one of the editors, Marco Beneventanus, prepared new maps of France, Spain, Italy, Scandinavia, central and eastern Europe and Palestine. With the exception of the Eastern European map, which was drawn by Bernard Wapowski, the other maps were based on those in the Ulm Ptolemy.

By now, the limitations of Ptolemy’s maps had become clear, and from the end of the fifteenth century onwards, the great overseas discoveries started to appear on printed maps. The 1508 edition (and late issues of the 1507 edition) of the Rome Ptolemy contains Johannes Ruysch’s map of the World, which is highly prized as the earliest available map to mark any part of the Americas.

Next in chronological sequence, and the most unusual of the editions of Ptolemy, was that published by Jacobus Pentius de Leucho in Venice in 1511, edited by Bernardus Sylvanus. Sylvanus, realizing the geography was outdated, attempted to update the maps by inserting more modern information, often from contemporary manuscript sources, over the Ptolemaic material, creating an unusual effect. An innovative feature is that the maps, which are printed from woodblocks, are printed in two colors, red and black, with the principal names in red. In addition to the Ptolemaic set, Sylvanus also included a modern map of the World, on a cordiform, or heart-shaped projection. Visible along the western border are eastern South America, Cuba and Hispaniola, and the tip of Labrador or Newfoundland.

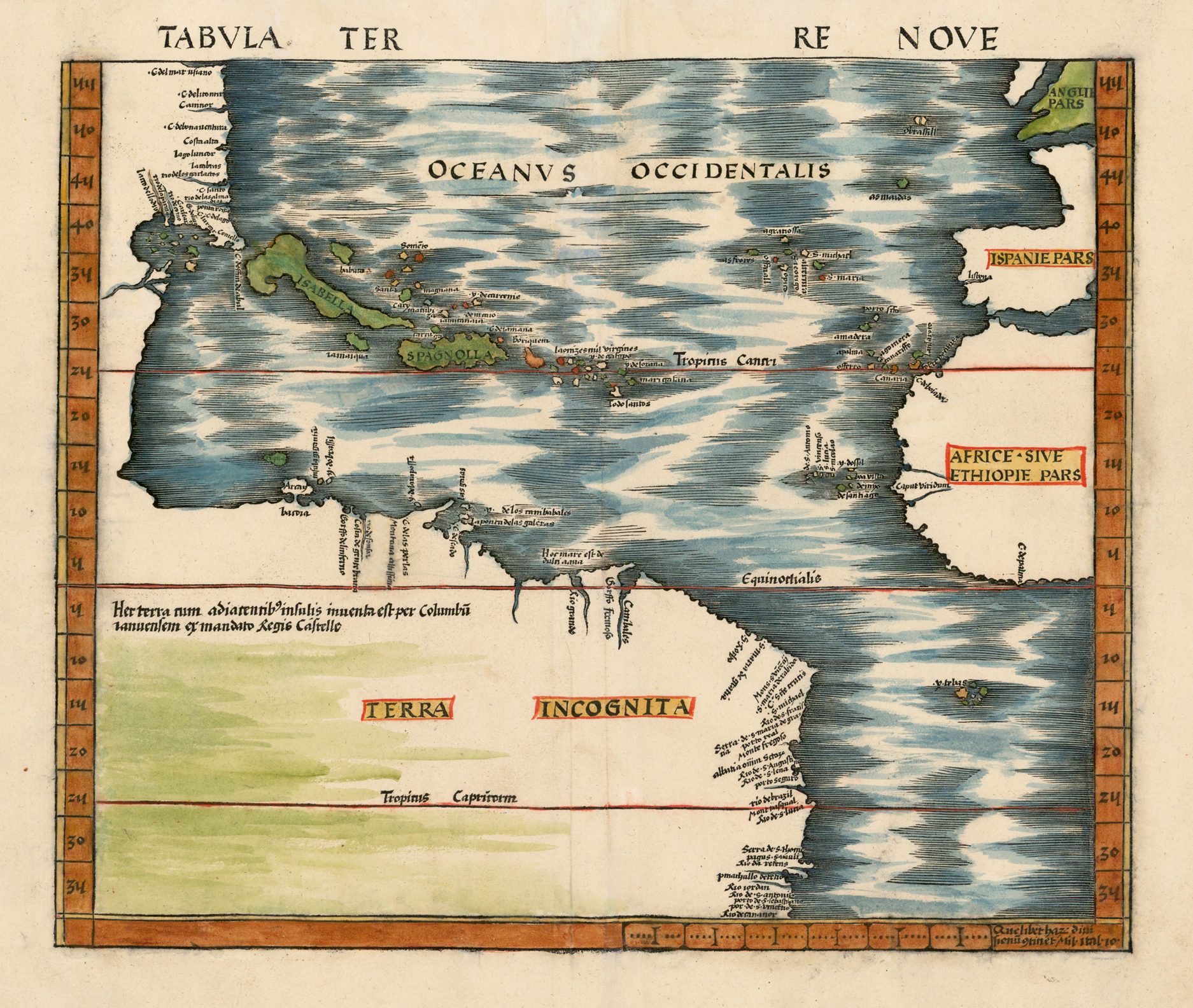

Martin Waldseemüller’s edition of Ptolemy, first published in 1513, is the most important of the sixteenth century editions. The atlas, with the maps printed from woodblocks, contains a separate, additional section, with twenty modern maps. This section has been described as the first modern atlas, as the first attempt to break away from the Ptolemaic tradition. The most important of these maps is a separate map of the West Indies and part of the Gulf Coast, which is the first in an atlas devoted to the Spanish discoveries in the New World, but there were also maps of Southern Africa, of the Middle East, and Southern Asia.

It has long been known that Waldseemüller’s edition had a difficult path to press. Much of the work was done in about 1507 or 1508, but it was not until 1513 that the atlas was actually printed. An important discovery, made by London dealer Jonathan Potter, has cast new light on the earliest phase of the development of the atlas. One of the modern maps added by Waldseemüller was of Lorraine. It is the only map in the atlas printed in color (black, red and brown). All the other maps were printed black and white. Recently, Jonathan Potter acquired an example of the Ptolemaic map of the British Isles (the first of the regional maps in the atlas), in which the sea area was printed in color, from a second block. This would seem to suggest that the initial plan was to print all the maps in this fashion, but for some reason, this plan was not carried through, presumably because of the technical problems involved.

Waldseemüller’s edition proved particularly influential, and served as a model for subsequent Ptolemaic atlases. As these atlases were relatively standard, the following notes will only highlight the more important additional maps added by subsequent editors.

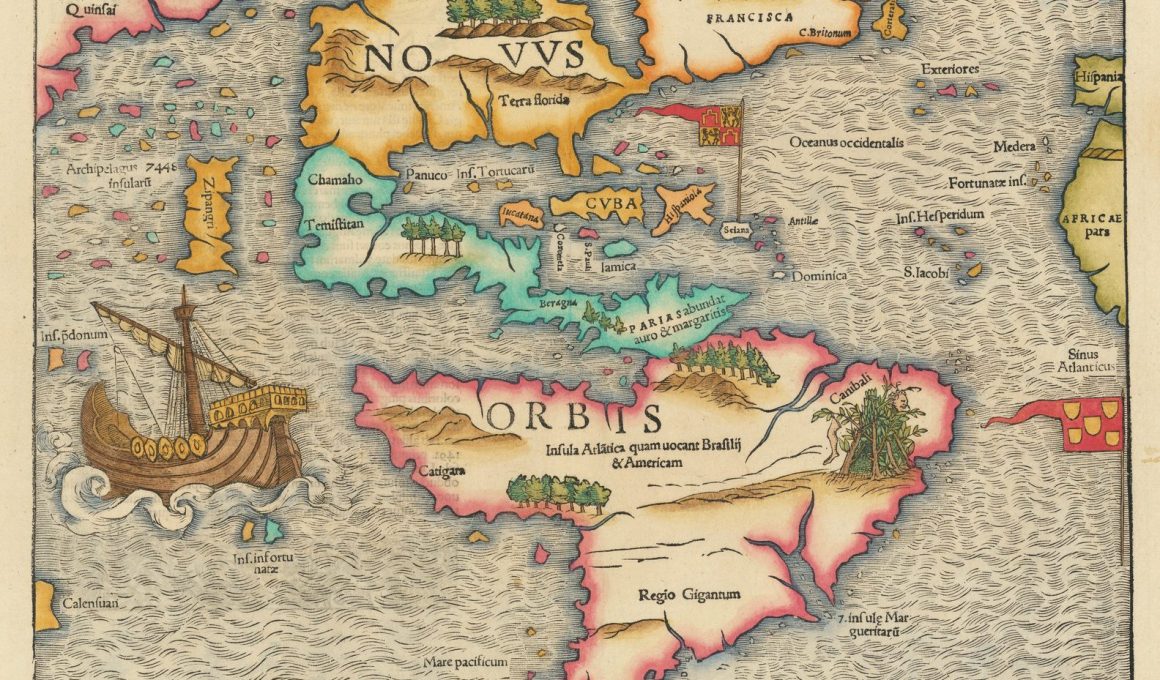

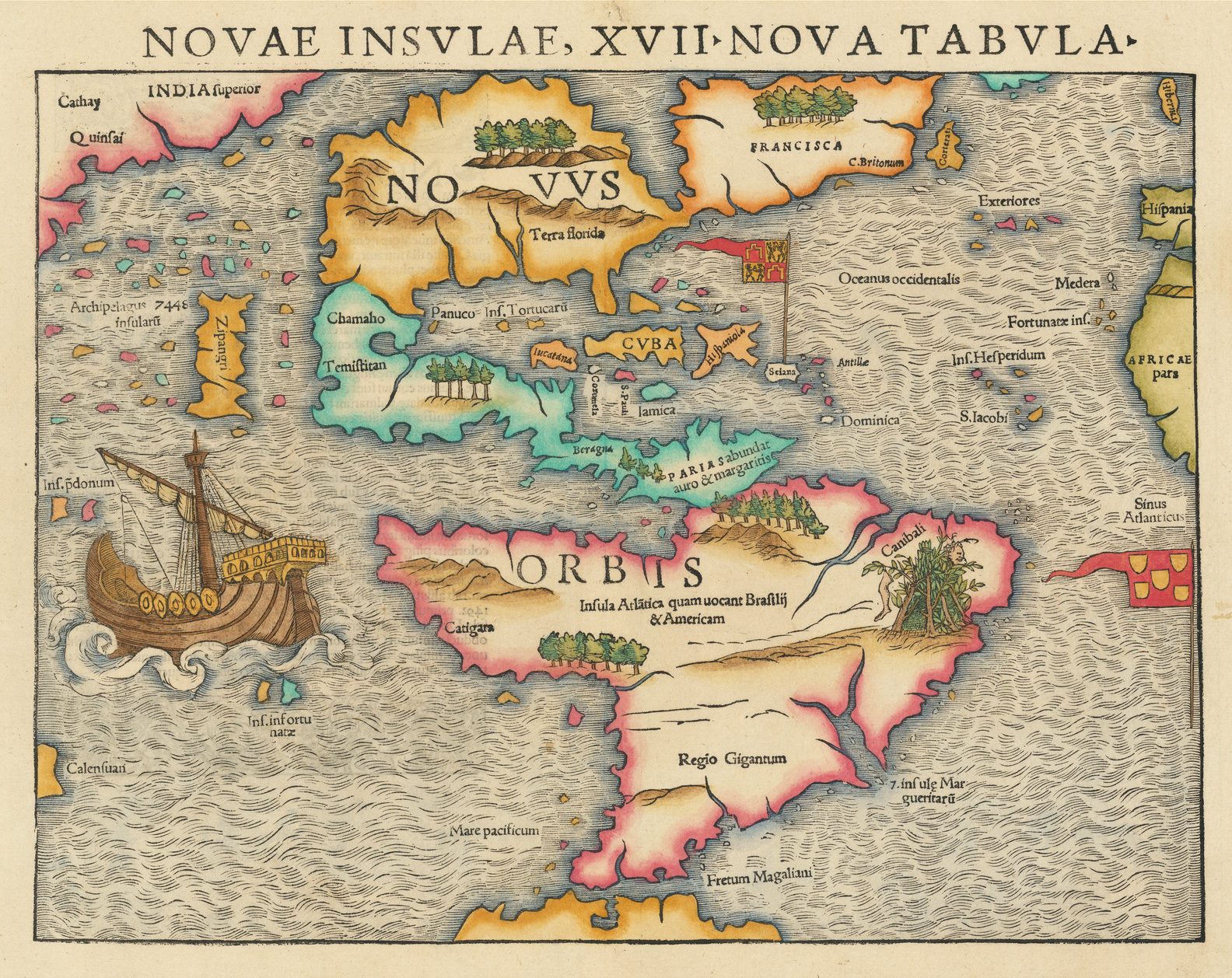

Waldseemüller’s edition was reprinted in 1520, and then the maps were re-drawn by Lorenz Fries on a smaller format, for editions published in 1522, 1525, 1535 and 1541. While largely a copy of Waldseemüller’s edition, Fries also added three new maps: a World map, the first in an edition of Ptolemy to name “America”, and the first printed maps of South East Asia with the East Indies, and of China and Japan.

The next to produce an edition of Ptolemy was Sebastian Munster, who worked in Basle. Munster was one of the leading geographers and cartographers of his period, and he diligently set about revising and improving the maps. His first edition, published in 1540, is notable as containing the first set of maps of the four known Continents. The Americas map is the first separate map of that Continent, while the other Continents had previously been depicted in other publications.

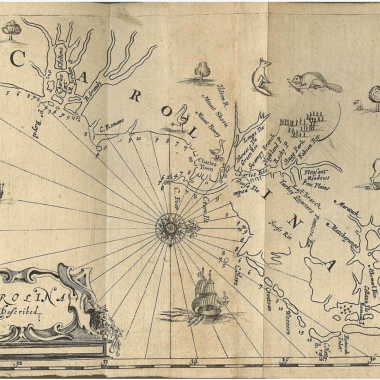

Giacomo Gastaldi, one of the leading cartographers of the sixteenth century, composed a set of maps for an edition of the Geographia, published in Venice in 1548. It is among the earliest examples of his work, in a long and distinguished career. This edition was the first pocket-sized edition. Despite being prepared on a small format, the maps are clearly and attractively engraved. Gastaldi was the first to add regional maps of the American continent, with important maps of the eastern seaboard, a map of what is now the southern United States, of South America, and separate maps of Cuba and Hispaniola.

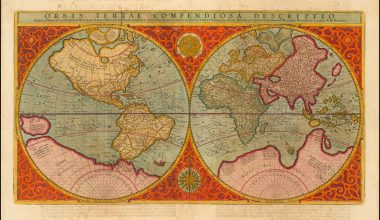

Gastaldi’s maps were re-engraved on a slightly larger format for an edition published by Vincenzo Valgrisi, in Venice, in 1561, and re-issued up to 1599. For this edition, Valgrisi (or the editor Girolamo Ruscelli) added four maps: a double-hemisphere map of the World (the first appearance of this projection in an atlas), a map of Brasil, and a map of the northern Atlantic, a copy of the “Zeno” map, which was alleged to have been drawn by two brothers, Nicolo and Antonio Zeno in 1380, and published by their descendant Caterino Zeno in 1558. While now considered to be faked by that descendant, the map is still a remarkably good depiction of southern Greenland and Iceland and, in the Valgrisi version, achieved a wide distribution.

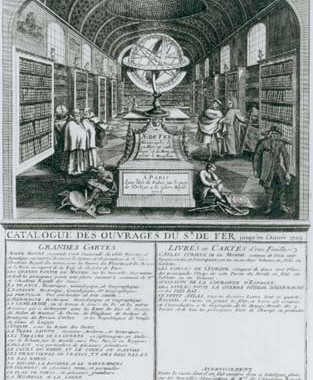

Of all the editions of Ptolemy, that prepared by Gerard Mercator, and published in 1578, is technically the finest, with the World map being a particularly fine engraving. By this time, Ptolemy’s Geographia had lost any pretense of being a “current” atlas. Instead Mercator’s intention was to produce an atlas of the classical world, that would serve as a companion to his modern atlas, as one part of a description of the universe. As such, Mercator attempted to return to the pure form of the original Ptolemaic atlas, discarding the modern accretions. As it happened, however, only the classical atlas appeared in Mercator’s lifetime. The atlas is, also, noteworthy for its longevity, the original printing plates were still in use in 1730, over one hundred and fifty years after they were first engraved.

The last two editions of Ptolemy to add new sets of map plates were published in 1596 and 1597. The first was published by Giovanni Antonio Magini in Venice in 1596, and almost immediately pirated by Petrus Keschedt, a Cologne publisher, with the maps from the two editions being almost indistinguishable.

For a series of maps that depicted the Hellenistic World of the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s maps and text had a remarkable longevity. In many ways, the popularity of the Geographia cast a heavy burden on publishers of the late fifteeen and first half of the sixteenth centuries, but the evident limitations of the work also proved an important incentive to individual mapmakers, such as Waldseemüller, Gastaldi, Mercator and others to look beyond Ptolemy’s work, and lay the foundations of modern cartography.