Antique maps have always been a popular collectable, combining the appeal and appearance of antiquity, while still being undervalued within the general ambit of antiques. There cannot be many fields where a collector is able to buy items from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries for a matter of a few hundred pounds. English collectors have always demonstrated a strong emotional attachment to their county, and this is often the basis of any collection, with John Speed’s maps the most famous, and most collectable. Yet, there is one series that transcends county affiliations to be among the most widely collected series of antique maps – those of John Ogilby.

In a remarkable life, spanning seventy-six years, John Ogilby pursued, with no little success, several careers, each ending in misfortune, and yet he always emerged undeterred, to carry on. Indeed, his modern reputation is based on his final career, started in his sixty-sixth year, as a publisher of maps and geographical accounts.

Ogilby was born outside Dundee, in 1600, the son of a well-to-do Scottish gentleman. While he was still a child, the family moved to London. However, when the elder Ogilby was imprisoned for debt, the young John had to go out selling “needles” and “spangles.” He invested his savings in a lottery, won a minor prize, and settled his father’s debts.

Unfortunately, not enough money was left to secure John a good apprenticeship; instead, he was apprenticed to a dance master. An ambitious young man, Ogilby was soon dancing in masques at court but, one day, while executing a particularly ambitious leap, he landed badly. The accident left him with a permanent limp, and ended his dancing career. However, he had come to the attention of Thomas Wentworth, later Earl of Strafford, Charles I’s most senior minister. Ever one to exploit his contacts, Ogilby became a dance instructor in Strafford’s household.

When Strafford was sent to Ireland, Ogilby accompanied him as Deputy-Master of the Kings Revels, and then Master of Revels. In Dublin, he built the New Theatre, in St. Werburgh Street, which prospered at first, but the Irish Rebellion, in 1641, cost Ogilby his fortune, which he estimated at £2,000, and almost his life. After brief service as a soldier, he returned to England, survived shipwreck on the way, and arrived back penniless.

On his return, Ogilby turned his attention to the Latin classics, as a translator and publisher. His first faltering attempt, in 1649, was a translation of the works of Virgil, but after his marriage to a wealthy widow the same year, his publishing activities received a considerable boost.

One means by which Ogilby financed these volumes was by subscription, securing advance payments from his patrons, in return for including their name and coats-of-arms on the plates of illustrations. As the prestige of his publications increased, so did the number of people recorded as subscribers. Another approach was to secure a patron, preferably in the court circle. Ogilby’s first patron was Strafford, who found out too late that all leading ministers are dispensable when Charles I assented to his execution in 1641. As he re-established himself, Ogilby sought a new patron, the King himself.

In 1661, Ogilby was sufficiently in favour to be approached to write poetry for Charles II’s coronation procession; he later published ‘The Relation of His Majesties Entertainment Passing Through the City of London’, and a much enlarged edition the following year, which included a fine set of plates depicting the procession.

In 1665, Ogilby left London to avoid the Plague then ravaging the capital. This was a minor disruption compared to the disaster he suffered the following year. In the Great Fire of London, Ogilby claimed, probably with some exaggeration, that he lost his entire stock of books valued at some £3,000, as well as his shop and house, leaving him worth just £5. On another occasion, he said he lost two-thirds of his stock, and this may be more accurate.

As he sought to restore his fortunes, Ogilby was already looking in new directions. The initial opportunity he seized on was the reconstruction of London’s burnt-out centre. He secured appointment as a “sworn viewer”, whose duty was to establish the property boundaries as they existed before the Fire. Ogilby was assisted in the project by his step-grandson, William Morgan, and by a number of professional surveyors. The result was an outstanding plan of London, on a scale of 100 feet to an inch, on 20 sheets, although it was not printed until after Ogilby’s death.

Perhaps identifying the new-found mercantile ambition of Restoration England, and wishing to exploit the potential, Ogilby turned his attention to publishing geographical descriptions of the wider-world. In 1667, he issued ‘An Embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China.’ This account was translated from the original Dutch text, and illustrated using the original Dutch views and plates.

Buoyed by the response to this volume, Ogilby conceived an ambitious project, a multi-volume description of the world, a project he described in a prospectus, dated May 10th 1669:

Africa, though not the remotest, yet furthest from our Acquaintance, the Author intends to be the First Volumn. America, being the next least known, the Second. Asia according to the same order, the Third. Europe, that hath been most Surveyed, of which much is to be said that hath not yet been Collected by any English Author, he designs to be his Fourth and Fifth Volumn; the last, but not the least in our Concerns, will onely contain the Business of Great Britain.

In fact, the volumes were joint collaborations, in conjunction with the Dutch publisher Jacob van Meurs. ‘Africa’, published in 1670, was the least original of the three, both in terms of the text, maps and illustrations. In a similar vein, he issued the ‘Atlas Japannensis’ (1670), the ‘Atlas Chinensis’ (1671), and ‘Asia’ (1673).

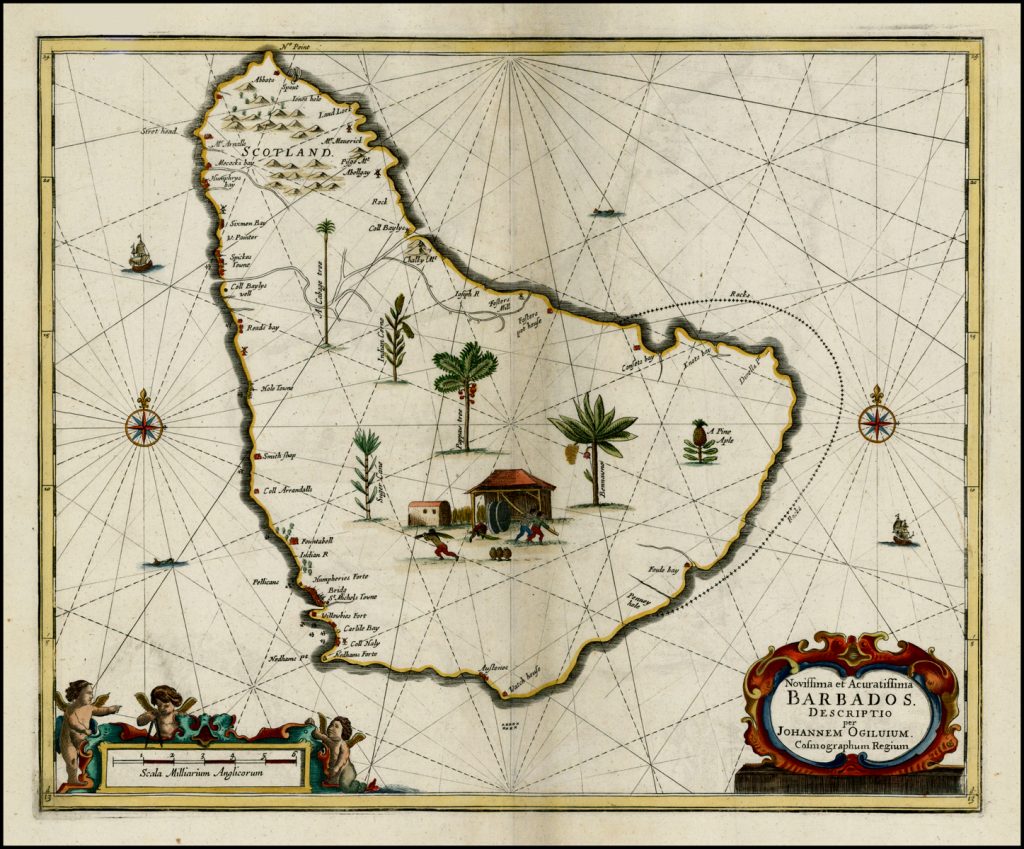

In 1671, Ogilby published the ‘America’, translated from Arnold Montanus’ Dutch text. However, Ogilby added fresh material on the English colonies. supplied by the Proprietors of the various colonies. Earliest issues contain only the Dutch maps and views, with the new English text. Later issues had a number of important maps, draughted from English materials, added, including a map of the Americas and very early depictions of Maryland, the Carolinas, Jamaica and Barbados.

The ‘America’ is certainly the most original, and most important, of Ogilby’s various geographical volumes, and its influence and popularity was immediate. With its completion, Ogilby turned to a project nearer his heart, the description of Britain.

Ogilby originally intended to devote one volume to Britain, but as the project evolved, he became more ambitious, as revealed in a prospectus issued in about 1672:

This having oblig’d our Author to take new Measures … to compleat within the space of two Years a Work … considering the Actual survey of the Kingdom, the Delineation and Dimensuration of the Roads, the Prospects and Ground plots of Cities, with other Ornamentals … into six fair volumes. The Four first comprehending the Historical and Geographical Description of England, with the County-Maps truly and actually survey’d. … The Fifth containing an Ichnographical and Historical Description of all the Principal Road-ways in England and Wales, in two Hundred Copper Sculptures, after a New and Exquisite method. The sixth containing a New and Accurate Description of the famous City of London, with the perfect Ichnography thereof …

In the proposals, Ogilby emphasised the scale of the undertaking; no-one before him had attempted such a vast project. He estimated the total costs would be £20,000, a staggering amount. The cost of the complete set of six volumes was to be £34. At that time, Wenceslas Hollar, one of the leading engravers working in London, could etch one printing plate a week, for which he might receive between £3 and £5. On an hourly basis, Hollar charged 1 shilling. Although that does not sound a great deal, Hollar could earn what was for most Londoners their daily wage, in one or two hours.

This proposal is important evidence for Ogilby’s grand plan, as the scheme ultimately foundered for want of money. Charles II promised £1,000 towards Ogilby’s costs, but never provided the money, and only £1,900 was raised in subscriptions.

Of the first volume, only three counties and three towns were mapped (Kent, Middlesex & Essex; and Canterbury, Ipswich & Maldon). Of the sixth volume, on London, only the general map appeared in print, and that after Ogilby’s death. In fact only one volume was actually completed. However, it is on this volume, the ‘Britannia’, that Ogilby’s reputation is founded.

The ‘Britannia’, issued in 1675, is a landmark in the mapping of England and Wales. After its publication, no map in England could be published without incorporating his information. Contemporary and subsequent map-makers rushed to pirate his work, without attempting to improve the information, yet, as with many great advances, Ogilby had merely put into effect a concept of amazing simplicity.

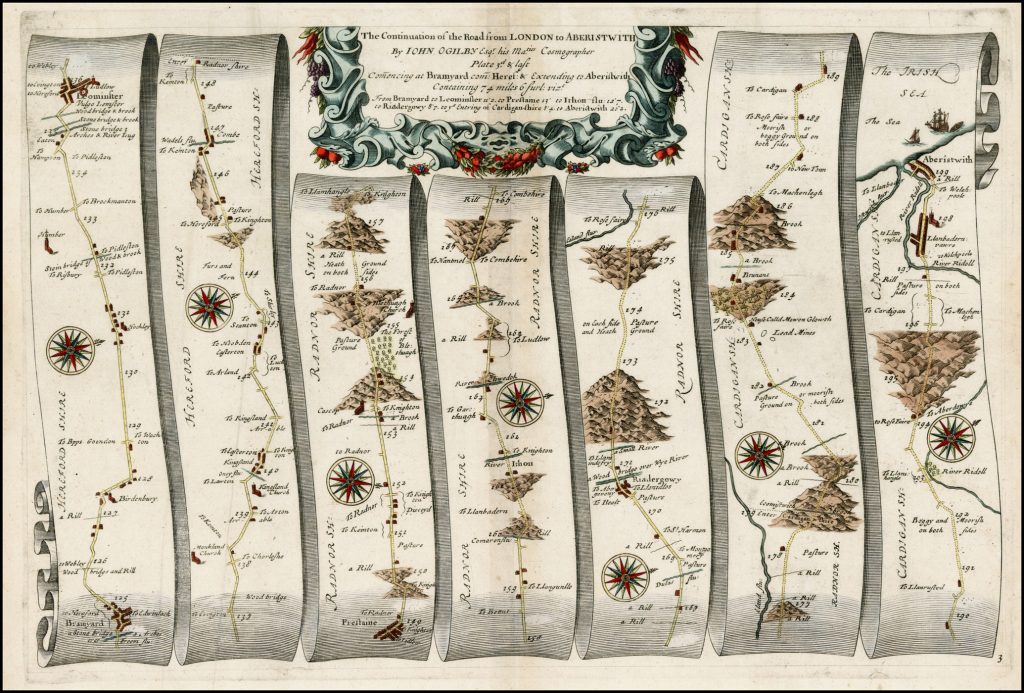

The ‘Britannia’ was the first national road-atlas of any country in Western Europe. It was composed of maps of seventy-three major roads and cross-roads, presented in a continuous strip-form. For the first time in England, an atlas was prepared on a uniform scale, at one inch to a mile, based on the statute mile of 1,760 yards to the mile. Ogilby claimed that 26,600 miles of roads were surveyed in the course of preparing the atlas, but only about 7,500 were actually depicted in print.

The atlas was composed of a hundred sheets of roads, with each covering a distance of about 70 miles. Longer roads, such as London to Lands End, were depicted on a series of sheets. On each map, the road is depicted in a series of parallel strips. The surveyors noted whether the roads were enclosed by walls or hedges, or open, local landmarks, inns, bridges (with a note on the material of construction), fords, and sometimes even the cultivation being practiced in the country on either side of the road. Hills were drawn to show the direction of their incline, and relative steepness.

One of the most interesting plates was the frontispiece, which illustrates the surveying techniques employed. The main requirement was to measure distance correctly; this was achieved using a way-wiser, or ‘Wheel Dimensurator.’ The wheel was pushed along, and displayed the distance travelled on the dial. A similar, though less accurate, device could also be fitted to carriages. Another important requirement was to denote the changes in direction of the roads, which is shown by compass roses, to overcome the schematic design. Similarly, the compass direction of significant local landmarks, such as church towers, windmills, large houses and so on, was established, and out-riders could then be used to ride to these landmarks, to take triangulation bearings. These techniques were also depicted in the title cartouches of four of the plates.

The ‘Britannia’ was an immediate commercial success. Although it is not possible to say how many examples were printed, four editions were needed in the first two years to meet the demand. Unfortunately, Ogilby’s business rivals were also quick to appreciate his work, and his information was quickly pirated by his contemporaries, who inserted the roads to up-date their maps of the individual counties. One of the earliest examples of piracy were four schematic diagrams added by Thomas Bassett and Richard Chiswell to their edition of John Speed’s ‘Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain’, published in 1676. In private correspondence, referring to this piracy, Ogilby complained that Bassett and Chiswell “have rob’d my book”.

In the following century, three pirate editions were published, in a pocket-format, which made them more convenient to use, and through this medium, Ogilby’s survey work remained in circulation into the 1760’s, a remarkable testament to the impact that the ‘Britiannia’ had.

In September 1676, Ogilby died. His stock passed to his heir William Morgan, who was encouraged to continue the projects. Morgan completed the map of London, but despite attempts to revive the British Atlas, no further volumes were to appear, and the existing printing plates were sold to other London map-publishers, bringing to an end one of the most ambitious and important attempts to map England and Wales.

Despite the many reversals of fortune he experienced, Ogilby left a permanent memorial in the ‘Britannia’, one of the two greatest English atlases published before the nineteenth century.

Among the many series of maps published before the nineteenth century, depicting the English countryside, available to the modern collector, the road maps of the ‘Britannia’ stand apart. No other series incorporates such a wealth of detail on the face of the countryside that the seventeenth century traveller would have seen as he passed along the roads, or displays it in such an immediate and comprehensible form for the contemporary audience.

Perhaps the most striking examples are those maps that depict the roads out of London; within only a short space of time, the seventeenth century traveller would have left the confines of the City of London, as he headed for Aberystwyth, for example. By the time the traveller reached Hyde Park, he was deemed in the countryside, and en route he passed through the villages of Camden, Shepherds Bush, East Acton and Acton.

All in all, Ogilby’s maps represent a fascinating record of the English countryside. Fortunately, his maps were printed in relatively large numbers for the period, so individual sheets are readily available for the modern collector, and are comparatively inexpensive, depending on the area shown.

Bibliography

Eerde, Katherine S. van John Ogilby and the Tate of His Times, (London: Dawson, 1976).

Harley, J.B. John Ogilby Britiannia (Biliographical Note to the Facsimile of Ogilby’s Britannia) (Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd, 1970).

1 comment