John Law was born in Scotland in 1671, the son of a Scottish banker. He received an education was in political economy, commerce and economics in London. In 1694, however, he was forced to flee to Amsterdam, after killing an opponent in a duel. There, he continued his education, studying banking.

In 1705, he returned to Scotland, and wrote a book Money and Trade considered, with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money (Edinburgh, 1705). The same year, he made a proposal to the Scottish Parliament for the establishment of a national bank, but his suggestion was turned down.

Thereafter, Law lived an itinerant life, travelling around Europe, seeking support for his various financial schemes. In 1715, he settled in France, and soon came to the attention of the Duc d’Orleans, regent for the young king of France. At the time, France was virtually bankrupt, partly a consequence of her lengthy and expensive foreign wars.

On May 20, 1716, Law was granted a licence establish a ‘Banque Générale’ in France. The initial capital of six million livres was divided into 1,200 shares, each of 5,000. The shares were payable in four instalments, one-fourth in cash, three fours in ‘billets d’etat.’ Law was authorised to issue notes payable on demand to the weight and value of the money mentioned at the day of issue, and on April 10, 1717, it was decreed that Law’s notes could be accepted in payment of taxes. The Banque Générale was very successful in regulating the paper currency, with the consequence that the interest rate fell to 4 1/2%, while the note issue rose to 60 million livres.

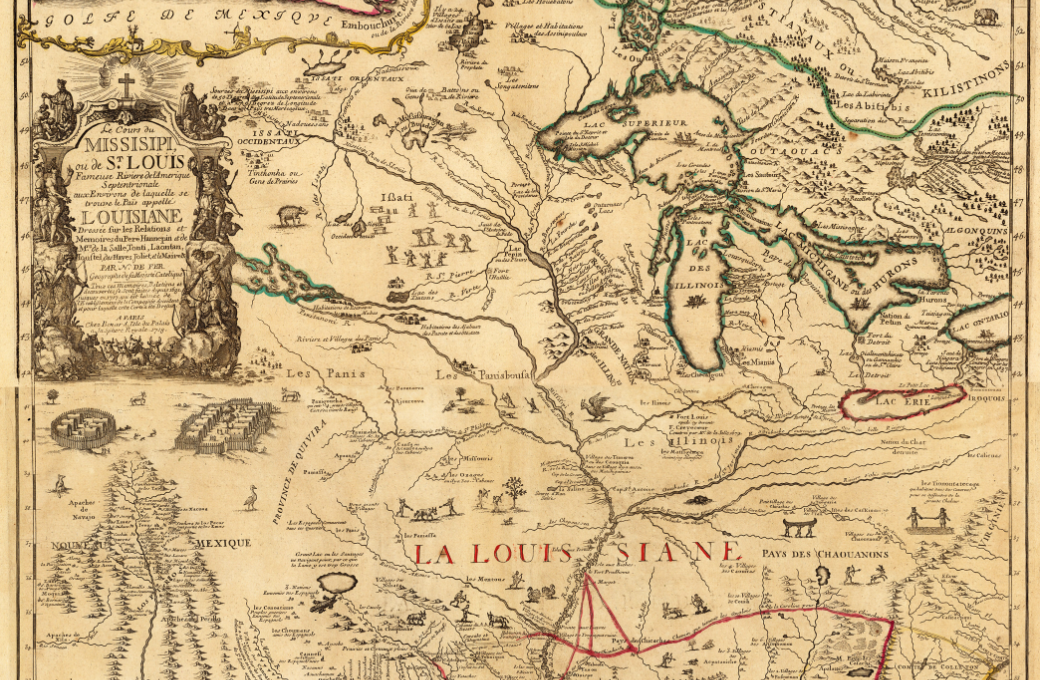

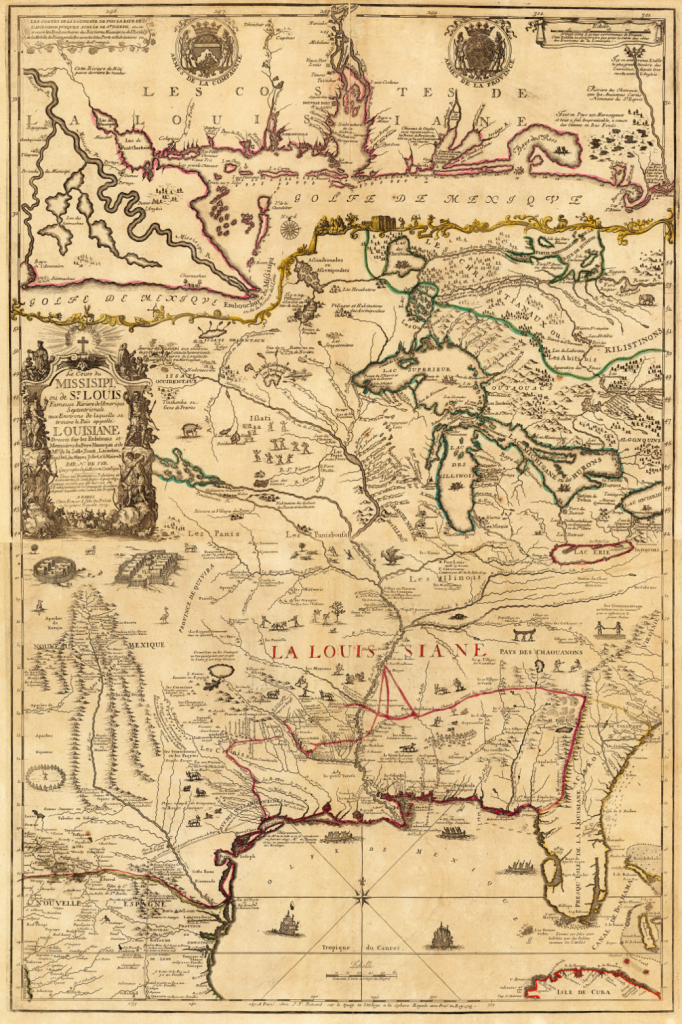

In August 1717, Law founded the Compagnie de la Louisiane ou d’Occident, which absorbed both the Louisiana Company founded by Antoine de Crozat in 1712, and the Compagnie du Canada. Law was granted extensive powers to exploit the Mississippi region – in French eyes the area of North America watered by the Mississippi, and its tributaries. When one considers that these tributaries include the Missouri and the Ohio Rivers, the French laid claim to a vast area, including regions also claimed by the British. The following year Law purchased the tobacco monopoly in this region.

Law’s proposal to exploit the apparently limitless resources of the region – the Mississippi Scheme – caused a tremendous wave of interest, not just in France, but throughout Europe, and this encouraged the development across Europe of several others overseas companies, for example the rapid expansion of the English ‘South Sea Company’ (founded in 1711), and a number of smaller companies in the Dutch Republic.

In December 1718, Law’s ‘Banque Générale’ was converted into the Banque Royale, with Law made a director. More importantly, the bank’s notes were guaranteed by the king. In 1719 the Compagnie de la Louisiane took over the Compagnies des Indes Orientales et de la Chine, with the new company being called the Compagnie des Indes.

By this time, Law’s reputation was truly in the ascendant. When he undertook to repay the national debt, in return for control of national revenues, and of the French mint, for a period of nine years, the share price of the Companie rose dramatically in a frenzy of speculation.

Shares in the Companie were originally issued at 500 livres, but rose to 10,000 lives in the course of 1719. When the Companie issued a 40% dividend in 1720, the share price rocketed to 18,000 livres, far-outstripping the capital base of the Companie. At this point, speculators resolved to take their profits. The share price dropped as dramatically as it had risen. As panic set in investors sought to redeem their bank notes and promissory notes, but the Companie did not have sufficient coin and went bankrupt. The effects were felt throughout Europe. Many European investors had invested in the French Companie and were ruined. Moreover, confidence in the other European companies was also destroyed, and these in turn went bankrupt.

Law, although undoubtedly a financial genius, was a victim of his inflated claims and also of his success. He fled from France, returned to his nomadic existence, and died, penniless, in Venice in 1729.

As one might expect, the mapmakers of the period also sought to profit from these grand schemes. In 1713, Nicolas de Fer issued a map of Louisiana, following the grant of the region to Antoine de Crozat. In 1718, this sheet was re-issued as part of a four sheet map of Eastern North America, apparently as an official publication for the Compagnie d’Occident. In 1719, a single sheet copy was published by Henri Abraham Chatelain, and another anonymous copy, probably by the Ottens family circa 1720.

In 1718, Guillaume de l’Isle published his ‘CARTE DE LA LOUISIANE ET DU COURS DU MISSISSIPI … 1718’. These two French maps show France’s territorial claims in the region, at the expense of English territorial claims. It is therefore very surprising that the London publisher John Senex copied de l’Isle’s map, retaining de l’Isle’s delineation of the French territories. Senex dedicated his map to “William Law of Lawreston”, probably a close relative of John.

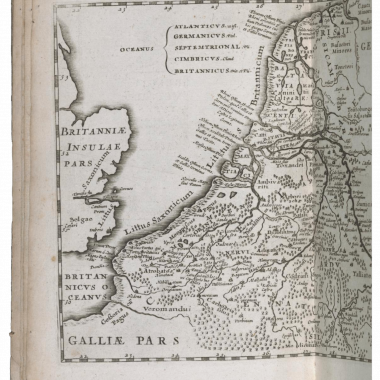

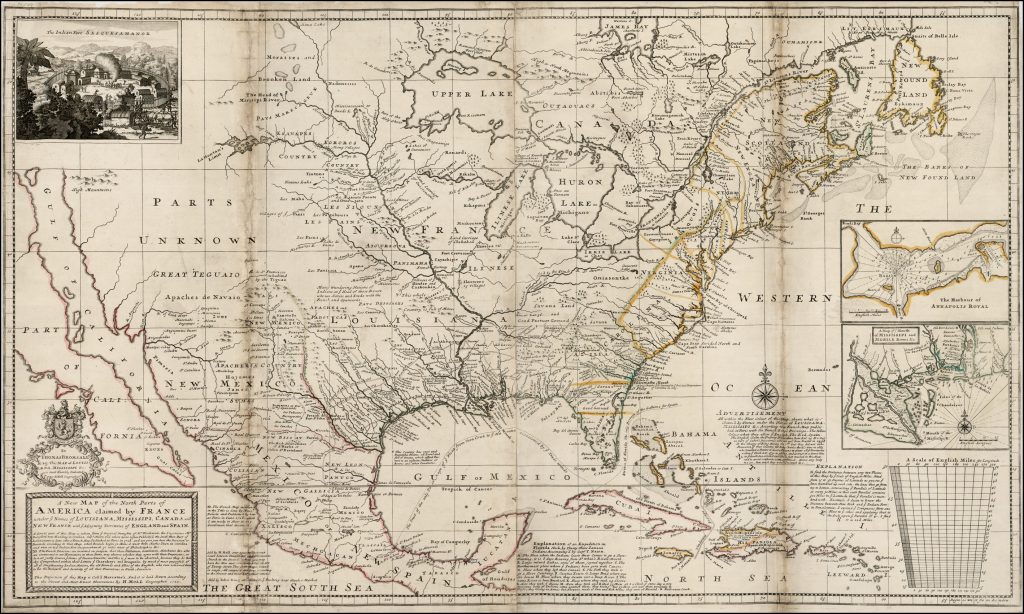

By contrast, the German mapmaker (and prominent Francophobe), Herman Moll, who lived in England from about 1678, fired the English counter-blast. His map of Eastern North America shows the French territorial claims, but then notes in the title:

“… NB The French Divisions are inserted on purpose, that those Noblemen, Gentlemen, Merchants, &c. who are interested in our Plantations in those Parts, may observe whether they agree with their Proprieties, or do not justly deserve y.e Name of Incroachments; and this is y.e more to be observed, because they do thereby Comprehend within their Limits y.e Charakeys and Iroquois, by much y.e most powerfull of all y.e Neighbouring Indian Nations, the old Friends and Allies of the English, who ever esteemed them to be the bulwark and Security of all their Plantations in North America…”

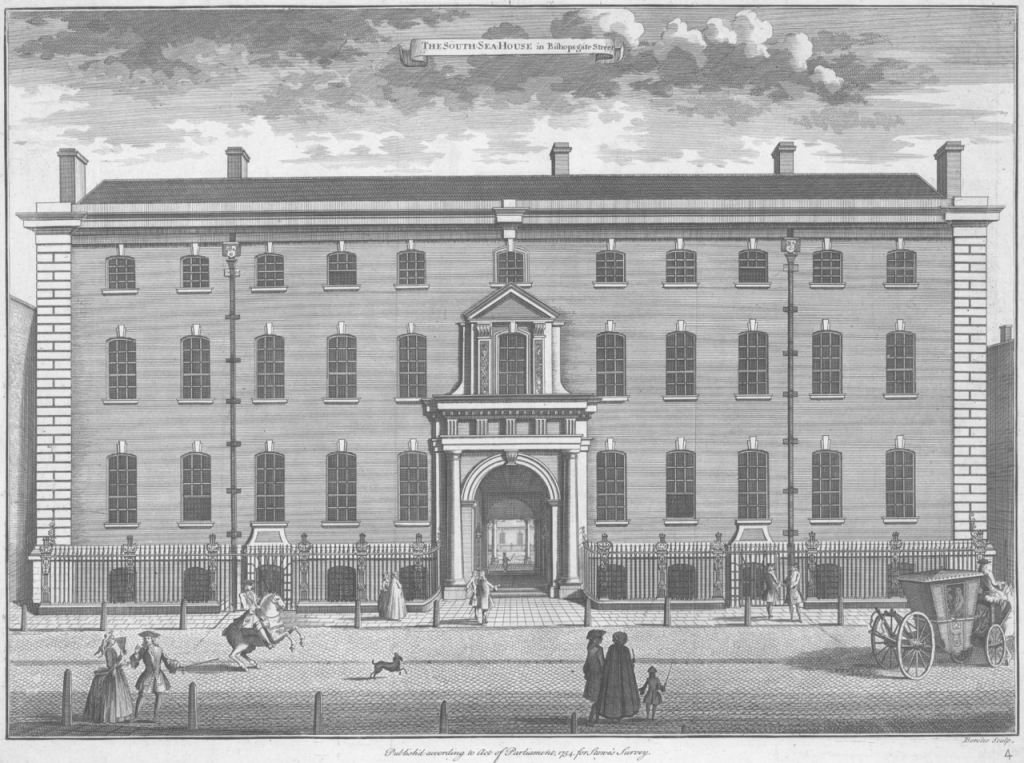

The English South Sea Company was founded in 1711 and was granted a monopoly over trade to South America and the Pacific Islands. The Company seems to have been run responsibly at first, and achieved considerable success, indicated by King George III becoming governor in 1718. However, the directors were spurred on by the French example and, in 1719, they offered to take over the national debt of £51 million for a payment of £ 3.5 million, and various other concessions. After competition from the Bank of England, the South Sea Company had to raise its offer to £ 7,567,00, an offer which was accepted in 1720.

The vast majority of the National Debt was held in the form of annuities. The Directors of the South Sea Company were relying on persuading holders of the annuities to exchange them for shares in the Company, but by inflating the share price, so that a large proportion of the annuities could be cancelled with the issue of a smaller value of shares. Apparently, over half the annuity holders readily accepted the offer, again in the belief of the potential profits to be gained. However, unlike the Compagnie d’Occident, the South Sea Company actually had no geographical presence, so its future earnings were always going to be problematic.

Once the Company had taken over the national debt, outside speculators and investors became more heavily involved in purchasing shares. In early 1720 the share price was 128 1/2d. In June, the shares traded for 890d, and in July they reached 1,000d.

At this point, prominent investors indulged in profit-taking, not speculators as in France, but the directors of the Company themselves. With the loss of confidence induced by the failure of the French scheme, the share-price collapsed, falling to 135 by November.

So serious was the matter, that the House of Commons set up a committee of inquiry to look into the affairs of the company. It soon became apparent that the Company had been falsifying its accounts to inflate its profitability. More significantly, widespread corruption was uncovered. The Company’s negotiations with the government had been advanced by the distribution of bribes to individuals within the government The principal recipient was John Aislabie, Chancellor of the Exchequer. So serious were his offences that he was thrown out of Parliament and imprisoned. Others implicated were the equivalent of the Prime Minister, Charles Sutherland, Earl of Sutherland, the Secretary of State and the Postmaster General, although none was convicted. It is also possible that King George I was involved.

As punishment, Parliament seized the assets of the Directors of the Company, raising something over £2 million, of which about £ 1.68 million was used to assist investors bankrupted by the failure of the Company.

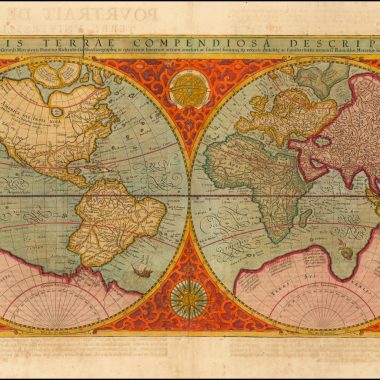

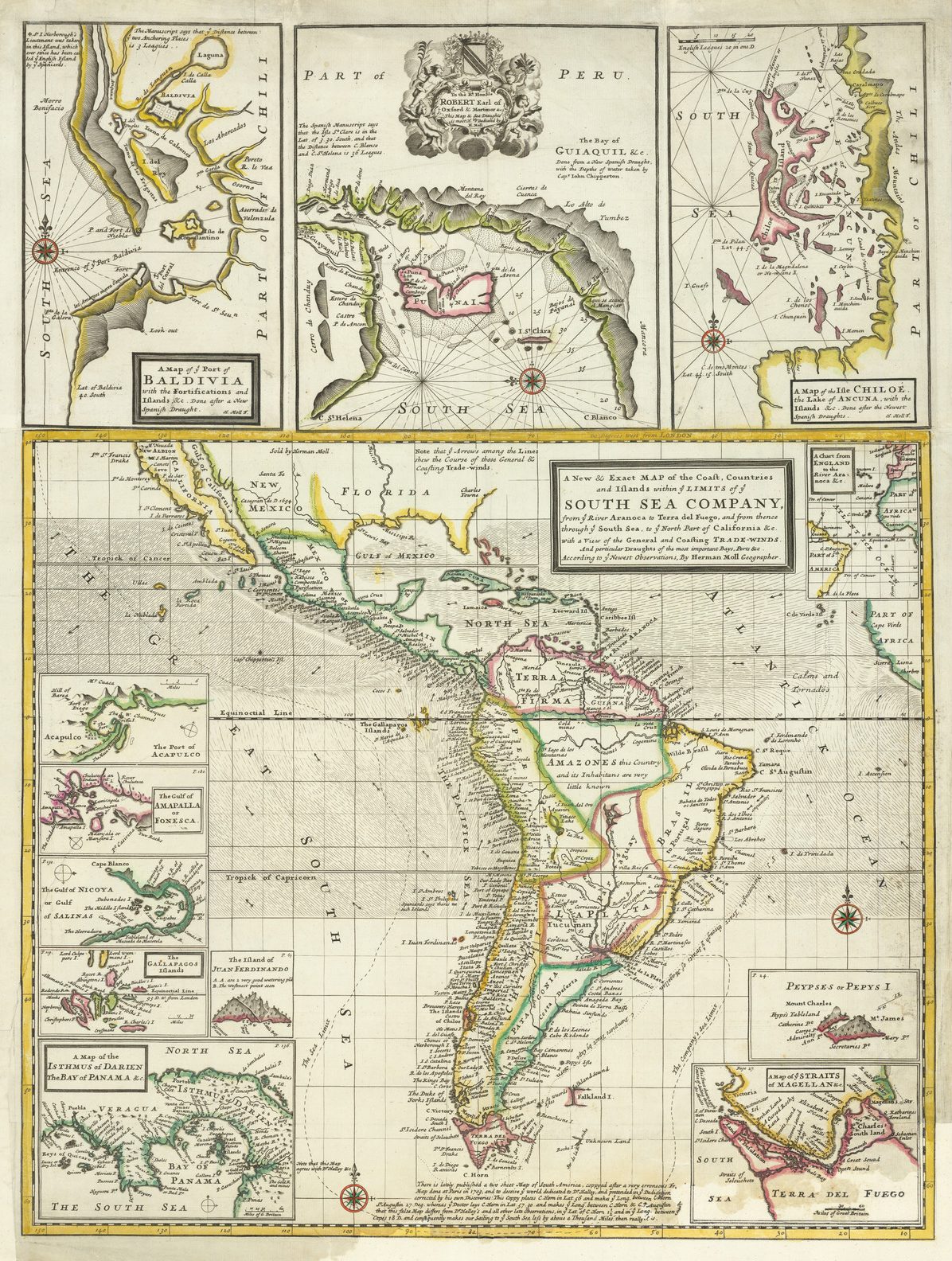

In 1711, F. Morphew published ‘A View Of The Coasts, Countries And Islands Within The Limits Of The South-Sea-Company’, with an introduction by Herman Moll (who may have been the author of the book), and a map of South America, showing the limits of the South Sea Company. This map was subsequently re-issued by Moll in his World Described. Illustrated here are Moll’s atlas version, which includes the additional panel of insets along the upper border.

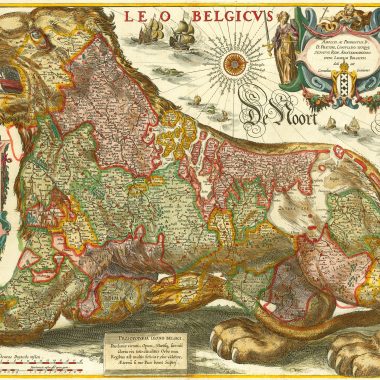

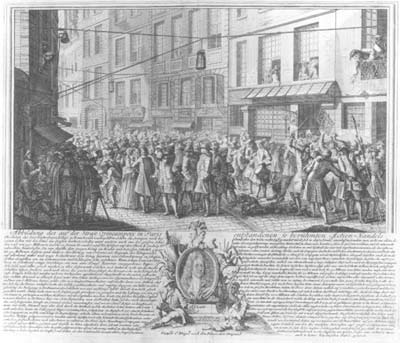

No sooner had the repercussions spread round Europe, than a number of artists and engravers published satires on the events, particularly the greed and gullibility of the investors involved. The most famous of the cartographic example is by L’Honoré and Chatelain, published in ‘Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid’ (Amsterdam, ca. 1720), a collection of engravings relating to the Mississippi, South Sea, West India and other ‘bubble companies’. Its Dutch title translates as “Representation of the very famous island of Mad-head, lying in the sea of shares, discovered by Mr. Law-rens, and inhabited by a collection of all kinds of people, to whom are given the general name shareholders.” A fuller description of this map is given in the Cartographical Curiosity section of this issue.

At the foot of the Monument (erected in memory of the fire of London), the inscription now reads ‘THIS MONUMENT WAS ERECTED IN MEMORY OF THE DESTRUCTION OF THIS CITY BY THE SOUTH SEA [COMPANY] IN 1720.

Circa 1721, an anonymous publisher issued an engraving ‘Great Britain’s Wealth & Safety.’, which was engraved by George Bickham Sr., and dedicated to the Honourable The South Sea Company., with the imprint, ‘Sold By A. Stockjober At The Two Brewers In Mine Street Southwark.’ The principal element is an engravings of ships of the South Sea fleet, apparently leaving harbour and sailing into the distance. On either side are two small maps, of Great Britain and South America. Above are two cornucopias, from which vast wealth is pouring forth.

Below the engraving is a satirical text:

Come all ye ruin’d Culls, now doom’d at last

To scratch your Ears & mourn your Follies past,

In miniature, behold your South Sea Fleet,

Bound God knows where, to carry on ye Cheat,

Well fraighted out, but, Fortune proving cross,

They spent their Cargo and return’d with loss;

As if the crafty Scheme at first was laid,

To flourish more my Fraud than foreign Trade.

Two horns of Plenty, also grace the Print,

Only top make a Pair, that’s all that’s in it;

If any should reflect, pray tell the Puppies,

They are not Cuckolds Horns, but Cornu-copiæs

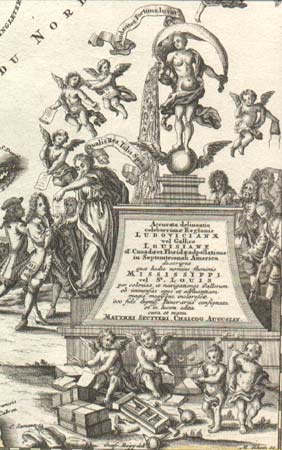

In about 1735 the German publisher Matthaus Seutter published a map of Louisiana, and the title-piece incorporates a satire on the Mississippi Bubble. Above the pediment stands a personification of the Mississippi, with the river flowing out of her shell. Within the waters can be seen all manner of riches, symbolising the wealth of the region. Other cherubs, and a female figure are selling paper shares in the Company to investors. In the background, two investors, no doubt speculators who have taken their profit, are sneaking away.

In about 1735 the German publisher Matthaus Seutter published a map of Louisiana, and the title-piece incorporates a satire on the Mississippi Bubble. Above the pediment stands a personification of the Mississippi, with the river flowing out of her shell. Within the waters can be seen all manner of riches, symbolising the wealth of the region. Other cherubs, and a female figure are selling paper shares in the Company to investors. In the background, two investors, no doubt speculators who have taken their profit, are sneaking away. At right is a cherub with an empty purse, above a group of distraught, and obviously ruined, group of investors, one of whom is about to fall on his sword. In the far distance, other investors are throwing themselves out of a tree. Two cherubs in the foreground are cutting up share certificates to show their worthlessness, while two others blow bubbles as a commentary on the scheme.

REFERENCE

Carswell, John. The South Sea Bubble, London, 1960.